San Miguel Acocotla a Tour of a Mexican Hacienda

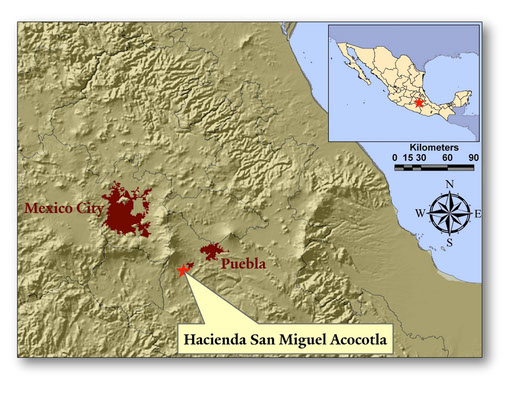

The Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla was founded in 1577 in Puebla's Valley of Atlixco by the Spanish colonizer Lucas Perez Maldonado.

Perez Maldonado was one of many Spaniards buying up land in the fertile valley. By 1610, his property was among the more than three hundred haciendas growing wheat for the markets in Puebla and Mexico City. Like the other hacienda owners, Perez Maldonado used the local indigenous population as his labor force.

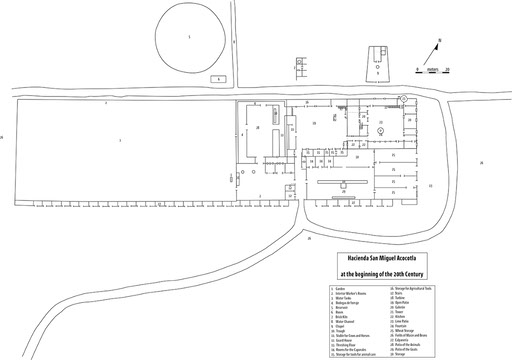

Over the next 350 years, the Hacienda Acocotla would have more than twenty owners. These owners gradually transformed Acocotla's landscape. By the last half of the 19th century, the Hacienda's buildings had expanded to become the large complex we see in ruins today.

One hundred years ago, these buildings housed the hacienda owner and his family, his manager, and as many as two dozen indigenous families. These families, descendants of the Aztecs, would have been responsible for the day to day work needed to keep the large farm running.

At the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla, 34 small rooms (together called the calpanería) would have housed the workers. Each room measured only about ten feet by ten feet, and each room would have housed an entire family.

Men, women, and children as young as four years old would have worked together in the Hacienda's fields from sunrise to dusk six days a week. At the end of the workday, the families would have gathered together in the field in front of the calpanería to relax, share a meal, and play.

On Sunday, the workers would have gone to mass in Acocotla's chapel with the rest of the community.

The workers would not have had any protection from the roving bandits who plagued the Valley of Atlixco during the 19th century because they were living outside the Hacienda's 15 foot high walls.

But not everyone was so vulnerable. A few families were more trusted. These workers got to live inside the walls with the goats in a space called "the goat patio."

The livestock and all the farm equipment were kept safe inside the Hacienda's walls, too.

The space allotted for the horses and cows, the "Animal Patio," was nicer than anything given to the workers.

The Patio Abierto, the "Open Patio," would have also housed some of the animals, along with many of Acocotla's agricultural tools and equipment.

Acocotla's manager had an office in one corner of the Open Patio, right next to the entrance to the hacienda owner's living quarters. Every Saturday night, the workers would have come to the office to collect their wages for the week. Adult men were paid 33 cents a day. Children earned even less, and we have no record of what women were paid, or even if they were paid at all.

The Patio of the Limes was back in the most remote part of the Hacienda Acocotla's buildings. It would have been a quiet space. The open space in the center would have had lime trees and a fountain. Surrounding it, two stories of rooms would have housed the hacienda owner, his family, and his guests in luxury. The rooms--bedrooms, living spaces, a dining room, and a kitchen--would have been beautifully decorated and painted in bright colors.

Historians have lots of information about how hacienda owners lived during this period, but we wanted to know more about the lives of the workers. These people, the majority of Acocotla's inhabitants, are virtually invisible in traditional historical documents.

So in 2004, we began a long-term research project in hopes of understanding more about the lives of the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla's workers. To do this, we used a combination of archaeological research, ethnographic research, and traditional historical research.

What did this mean? We set about digging up the lives of workers at the hacienda, talking to their descendants in a nearby village, and combing through old documents in regional archives--all in hopes of catching a glimpse of their day-to-day lives.

In 2005, we put shovel to earth and started uncovering the detritus left by Acocotla's indigenous inhabitants. We spent four weeks exploring the calpanería and the field in front. In 2007, we returned for another eight weeks of digging.

By the end of the two field seasons, we had dug five of the rooms in the calpanería, mapped the hacienda's architecture, and located a large midden (or trash pile). In the process, we had collected 87,142 artifacts, each one a clue to how the people at Acocotla had lived their lives.

As we dug, we found the remains of the lives of Acocotla's workers. We bagged up everything from fragments of the cups they drank out of to the tools they used in the fields to bits of jewelry and charms for healing.

One hundred and fifty years ago, someone harvested wheat with this scythe. We found it buried under a collapsed roof in one of the calpanería's rooms.

This bronze figa is a fine piece, an expensive charm bought to protect a child from illness and curses cast by witches. What story does it tell? Of course it shows us that parents worried for a child, not surprising in a time when half of all children died before the age of five, but what else?

Unexpectedly, the most intriguing part of this object's story was, in fact, how common it was. An identical charm was found in excavations at St. Augustine in Florida. These two pieces, found so far apart, were clearly mass-produced back in Spain. The charm has an ancient history in Europe where it has been used to keep the Evil-Eye at bay for hundreds upon hundreds of years.

At Acocotla, the figa reminds us that though we often assume indigenous people were "superstitious," in fact, the Spanish conquistadors brought their own magic to the Americas.

Most of the things we found were more mundane. Who hasn't lost an earring?

We found a number of unpaired earrings at Acocotla, but these two are particularly evocative. They are nearly the same design, but one is hand-made out of fine materials--gold and coral--while the other is machine-made out of tin and glass.

Why such similar designs? Did a woman lose an expensive gold earring and buy a cheap replacement? Did a neighbor covet the earrings of her friend, purchasing a cheap copy in an attempt to capture a bit of the glamour for herself?

The archaeology left us with as many questions as answers. So we dug into people's lives with more than our shovels.

One hundred and fifty years ago, the people living in the village of La Mojonera worked at Acocotla. We took our clipboards, tape recorders, and cameras into the modern day community and asked people about the stories they had heard from their parents and grandparents, and about their own memories of the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla.

We heard a lot of things we expected to hear. Hacienda labor was difficult. Hacienda owners were cruel. They were so cruel, they must have made a pact with the devil.

These are the stories that the official history, the history found in textbooks, leads us to expect. Life in the past was hard.

But for many, life now is pretty hard, too. One woman, who had lost all her children to either illness or migration, yearned for a day when a paternal hacienda owner sent a doctor to look after a woman's children. She said to us, "Now I am alone like a dog with no master..."

In spite of the hardship, life in the village today is full of moments of joy and celebration. Over the years, people shared their memories and their food with us, and taught us a lot about what life at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla was like.

Want to learn more? Check out the book!

For more information about the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla, the people who lived there, and the history of Puebla, get a copy of my award-winning book, "Biography of a Hacienda."