Comin' Up Saying goodbye to the gang life

The last day of Juan Velasquez’s junior year was one he said he'll never forget.

“I remember it, the last day of high school,” Velasquez said. “I had a revolver pointed at my head and I was lucky he didn’t shoot.”

It sounds like a scene from a movie, but for Velasquez, staring into steel came with the territory...another day in the life of a gang member.

“We were getting in trouble...shooting, getting shot at, tattoos, drugs, getting drunk, getting high,” Velasquez said. “We started smoking at maybe 11 years old."

Velasquez could’ve been another gangbanger caught in the perpetual cycle of drugs, gangs, and prison. Instead, Velasquez shifted course and found a way out of the streets and into a job. Velasquez is one success story of Fort Worth's gang-involved youth who are working to find a way out.

Living in the shadows

They’re easy to miss. You might not even know they’re still around. They live and operate somewhere in the shadow of the city’s cowtown culture, but gangs are just as present today as they were in the bloody summer of ‘93.

The 2015 Texas Department of Public Safety Gang Threat Assessment reported more than 5,600 gangs in Texas with over 100,000 active members. The DFW area has one of the highest gang concentrations in the state and more than 260 gangs have been identified by the Fort Worth Police Department Gang Section. Those gangs embrace over 12,500 members in Fort Worth alone, according to the report.

Nestled deep in the crevices of the city are Fort Worth’s hoods, where the colors that matter are the ones you wear.

The Fort Worth hoods, covering south of Interstate 30 and east of Interstate 35W, often get overlooked by Dallas, but sections spanning across Stop Six to South Side are putting on for “Funky Town.”

At the heart is South Side, with areas of Agg Land and Hoova Land, or the old Terrell Heights community. You have Como after Terrell Heights. Then Stop Six, the stomping ground for Bloods. Riverside and Polywood (Poly) host the Latin Kings, HCs and Crips. The Four Trey Gangsta Crips, Murdaworth Mexicanz, and Tango Blast run Northside, to name a few.

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s drugs ran the city and gangs ran the drugs. The Stop Six Bloods, EastWood Pirus and Hoovers in South Side put Fort Worth on the map, earning the city the title "MurdaWorth." During the summer of ‘93 the gangbanging body count reached well over 60, according to an officer’s report in a ‘99 Star-Telegram article.

“The Stockyards, back when I was growing up, used to be low riders cruising down Main Street, people drinking, gang fights, all kinds of crazy stuff,” Velasquez said. "I grew up seeing that lifestyle.”

The gang culture across the nation has widely changed since the ‘90s. There’s less violent animosity over turf. Once rival gangs, like Bloods and Crips, can be seen working alongside each other. There’s a smaller culture of all-out violence and more focus on blending in, making music, and conducting business behind the scenes.

Lori Cooper works at the Boys and Girls Club Poly location. She's a director of the Comin' Up: Gang Intervention program, which helps gang-involved youth get off the streets at night and gain education and job skills.

“We’re seeing a changing trend among gangs,” Cooper said. “They’re getting much more sophisticated. Some gangs are mandating that new initiates get their GED and job skills.”

One of the largest changes in gang culture, though, is age. Gangs are recruiting younger and younger. Gangs that used to be cultivated in prison and high schools are now being built on the playground.

A way to survive

Some choose the gang life, and for others, the gang life chooses them. For Velasquez, and so many others, there’s no choice at all.

“It used to be kids joined because of isolation and lack of education,” Cooper said. “Now they’re thrust into the chaos.”

Many kids grow up with a support system. They have the crust cut off their bologna sandwiches. They’re focused on getting good grades and ruling the playground. For Velasquez, it was different.

Velasquez was born in Mexico. His family illegally immigrated to America when he was five and transplanted themselves in Fort Worth’s Northside neighbourhood. School was a fundamental problem.

“I can go to school until a certain point and then I have a block,” Velasquez said. “My legal status puts a block on me. With that in the back of my head I thought, ‘you need a way to survive.’”

With a father that was constantly gone for work, Velasquez looked to the Northside community to be his family.

“My dad was always working and never really paid attention to me, so I looked for that love and attention from somebody else,” Velasquez said. “That’s how I got involved with gangs and drugs. I followed in my cousin's’ footsteps. They joined a gang and I joined right after them.”

Velasquez joined a gang when he was a child and by sixth grade he was a dealer with a criminal record. Growing up, it was more than making easy money. It was survival, Velasquez said.

For young initiates, the stories are all similar, but for the kids at Stop Six, Riverside, Northside, and Poly, they couldn’t feel more alone.

“It’s sad,” said Cooper said. “These kids are all experiencing the same thing, but they are so closed off in their own neighbourhood it’s kind of like tunnel vision.”

For some boys in Stop Six, like Velasquez, initiation into a gang is almost a birthright.

One boy, who requested to remain anonymous, said he became a Blood when he was 12.

“I had to take care of my family,” he said. “My mom worked hard, but it wasn’t enough. I had to bring some money in to support my little brothers and sisters.”

Dealing drugs, gambling, and doing whatever else was needed of him gave the boy the funds he needed to support his family and then some. His crisp white Jordans and shiny jewelry served as a testament to his earnings.

But it all comes with a cost.

“It has it’s ups and downs,” the boy said. “When you’ve been doing it so long, it becomes a part of you.”

The boys in Stop Six spend hours chilling, gambling, making music, and smoking at the park. When it's time for business, though, things heat up.

“When it’s time to ride, you ride,” the boy said.

Riding comes with the risk of injury, getting locked up, or death. Most members don’t make it out unscathed. Many young members spend some time in juvenile detention at least once.

Velasquez got arrested for selling weed and did a short stint in Kimbo (a nickname for Fort Worth’s juvenile detention center) while he was in sixth grade.

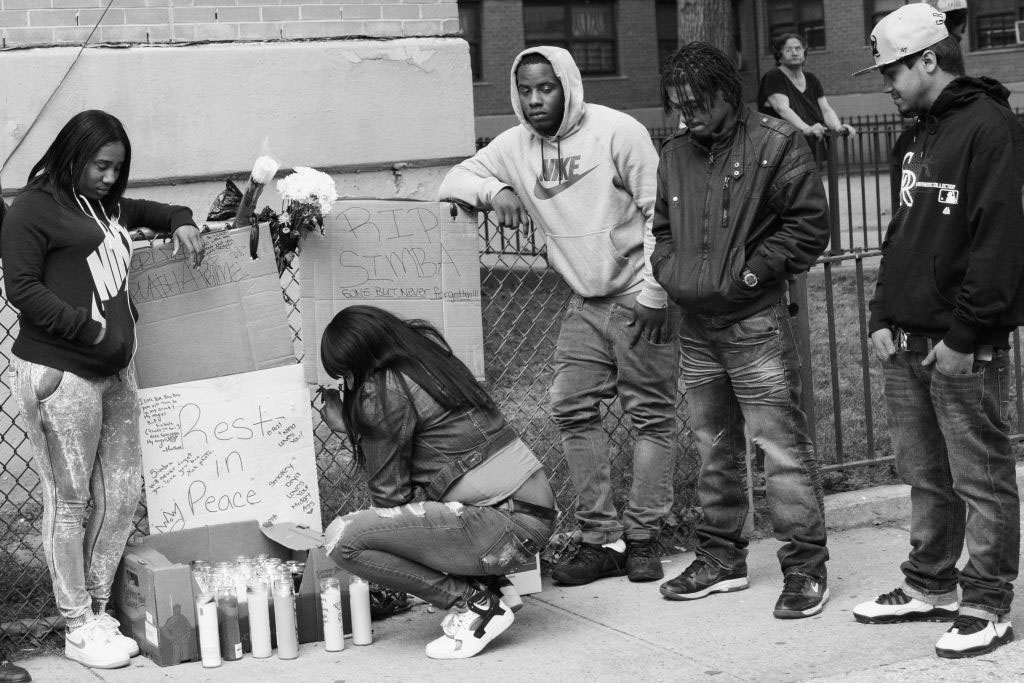

While it’s common to go on “vacation” for a stay at Kimbo, death is something the youth know far too well.

“I lost my cousin in a gang shooting last year,” the boy said.

Two other boys from the same gang said that they recently lost their cousin in a drive-by shooting three months ago.

It all takes its toll.

Comin’ Up

As an escape and a safe haven, Velasquez and the boy from Stop Six, along with around 1,000 other gang-involved youth in the city, turn to the Fort Worth Boys and Girls Club Comin’ Up: Gang Intervention Program.

The program is in partnership with the city of Fort Worth to provide need-based services and activities to help reduce gang violence.

“I joined the program because I wanted to change,” the boy said. “I’ve seen so much.”

He joined the program two and a half years ago and goes to the Stop Six location almost every day that he can. Since joining the program he’s gotten a job and has held employment for 90 days.

The Comin’ Up program gives kids from 13 to 25 a place to get off the street and gain their GED and job skills like forklift training and other certifications. During group sessions they talk about real-world issues like drugs, sex, civil unrest, and more.

The program also provides kids a safe place to let off steam. There's an open gym where members can play basketball, teen rooms with pool tables and TVs, and some locations have sound booths to record music.

The Comin’ Up program has locations in all the major hoods. Each location serves different gangs, but the results are similar. Gang-involved youth are standing on their own and creating a name for themselves.

Velasquez joined the Northside program when he was a teen. It was a chance to stay on the right path and not be distracted by gang life outside of school.

“While I was in school it wasn’t bad, but outside of school was a whole different story,” Velasquez said. “Having to see my mom through a glass door picking me up at jail...it was a rude awakening. I didn’t want to put my mom through that again, so I started changing my ways.”

At Northside, Velasquez received his GED and learned welding skills. The program also helps its members gain their citizenship and Velasquez is in the midst of that process. Now in his 20s, Velasquez holds down a top position at a welding garage.

“Thanks to Brian, the program coordinator at Northside, I am where I am now,” Velasquez said. “I still wear black and grey every day. I’ll be in ‘til I die, but I’m not doing the crazy things I was before.”

The program coordinators at every location are devoted to the kids. Each has a different nickname given to them by the members.

Cooper, “Squeaky” as the kids call her, has been the program director at the Poly location for eight years. She knows every kid's name and their story. Cooper said the program is more than just a place for kids to go after school - it's a refuge from turbulent home lives and a starting point for success.

“These are kids that so many people don’t want to see succeed and don’t want to see make it,” Cooper said. “They’re our future. They have to find stability.”

The kids are finding that stability, too. The members are regulars. If they're late or skipping a day, Squeaky knows exactly what they're doing. Every location is a surrogate family and so much more.

Jurrell Washington “Bam Bam,” 17, joined the Comin’ Up program five years ago. He said he chose to join in hopes of finding a new life.

The Comin' Up program helped Washington get back on track with school work and gain admission into a trade school where he attends night class.

“Poly is one safe place,” Washington said. “This program has helped me get into auto mechanic school.”

Washington goes to the Poly location three times a week and he said he’s gained so much more than just job skills.