Amongst the Canyon Walls Traversing the length of the grand canyon by foot

Text: Elyssa Shalla

Photography: Matt Jenkins

Matt and I were driving from the South Rim towards Las Vegas. It was early March 2015. The sky was blue and the temperature was warming up. We were looking forward to spending the next few days biking, running, and climbing at Red Rocks. As we drove along, we were talking about adventures. I posed the question, “How about hiking the length of the Grand Canyon this winter?” Not surprisingly there was a lengthy pause in the conversation, then some cursory questions were volleyed. By the time we drove past the turn off for Pearce Ferry we’d reached a consensus. We were going for it. Henceforth, traversing the length of the Grand Canyon by foot became our BHAG.

What’s a BHAG? Gavin McClurg explained that a BHAG is a Big Hairy Audacious Goal. It's something that you’ve never done before and maybe no one else has ever done it. The stars are going to have to align. You might need a little bit of luck. You might need a wind at your back.

You are truly, sincerely, when you look in the mirror, not completely convinced even to yourself that you can pull it off.

What makes hiking the length of the Grand Canyon such a BHAG? Many, many things. Let’s start by considering the scope of the canyon. Grand Canyon National Park encompasses more than 1.2 million acres (approx. 2,000 sq. miles/5,000 sq. kilometers). The name Grand Canyon implies that the abyss consists of only one canyon, but actually there are more than 600 canyons here.

These canyons are tributaries of the Colorado River. Tributaries split in half and split, and split again. Counting branch by branch, the tributaries eventually number in the thousands. Various portions of the Grand Canyon along the 277-mile stretch of river that flows between Lees Ferry and Pearce Ferry have vastly different terrain, and each canyon inscribes a signature so descriptive that it is difficult to talk about more than one at a time (Childs, 1999). "The canyons," Childs said, "are only similar in that they often involve rock and cliffs and some sign of water. That is all. Few of the canyons have names. Fewer have trails. In most decades will pass between human footprints."

THRU-HIKING

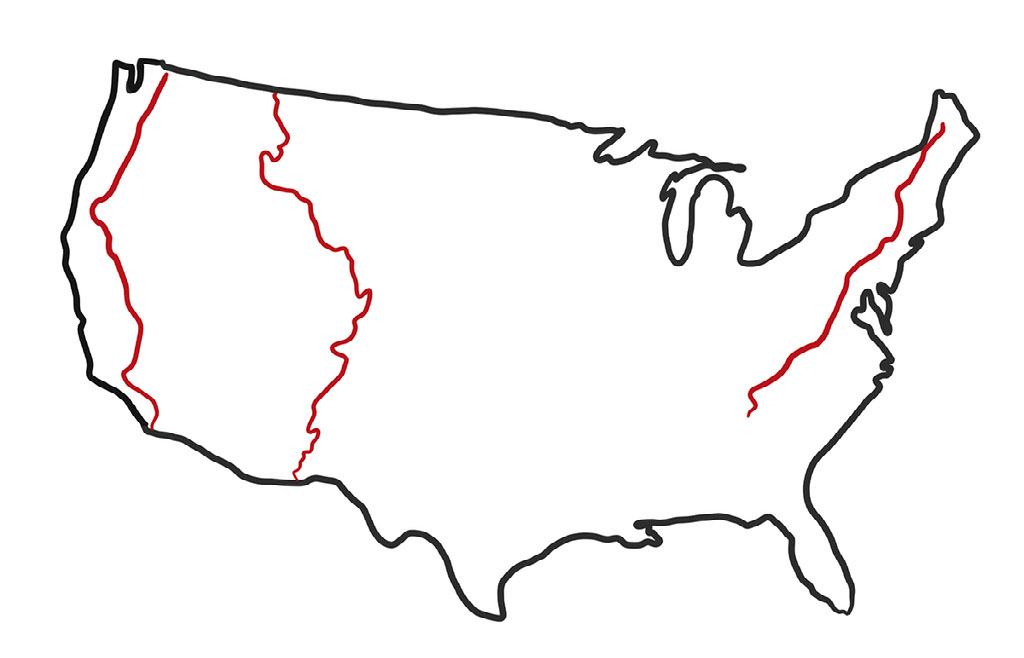

In the United States, long distance hiking is now more popular then ever before with record numbers of people setting out to thru-hike and section-hike our nation’s scenic trails. In 2014, 799 people hiked over 2,000-miles on the Appalachian Trail (AT) which extends from Georgia to Maine. In 2015, 618 people completed 2,600-miles on the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), while 32 people walked 3,000-miles along the Continental Divide Trail (CDT) between southern New Mexico and Glacier National Park. At the beginning of 2015, only 24 people had ever hiked the length of the Grand Canyon, half by section-hiking and half by thru-hiking (Martin, 2015). So, how does thru-hiking the length of the Grand Canyon compare to a journey upon the AT, CDT, or PCT? It doesn’t. Distances, terrain, remoteness, and a lack of consolidated information make a Grand Canyon thru-hike a markedly different undertaking.

In terms of mileage, a Grand Canyon thru-hike pales in comparison to these longer trails. If the length of the canyon is considered to be 277 river-miles, then a traverse of the canyon on land is going to be a minimum of 600 foot-miles. Due to the numerous tributaries and their sheer, vertical cliffs, a hiker must often detour a long ways away from the river. As a result, one river-mile is approximately equal to 2.2 foot-miles (Myers, 2013).

One of the biggest differences between hiking the length of the Grand Canyon and hiking the length of the AT, PCT, and CDT is the word trail. In the Grand Canyon there is no trail or established route that connects one end to the other on either the north or south side of the Colorado River. Even walking the 122-mile Tonto Trail system from Garnet Canyon to the Little Colorado River, only nets you 54.5 river-miles. For at least 75 percent of the journey on the south side there is no trail. On the north side of the river, there is less than 10 percent trail. Which means that the remaining 90 percent will be off-trail hiking (Myers).

The terrain encountered in the Grand Canyon may be some of the most difficult on the planet. You may have heard or read stories of people who one day decide to quit their job, go to REI and buy a backpack or pull an old dusty pack off the shelf in their garage, and hitch a ride to Campo, California where they start walking north on the PCT without having been for a hike in the past couple of decades or maybe ever in their life. When it comes to hiking in the Grand Canyon there is no opportunity to get fit on the trail. It is not possible to hike the length of the canyon off the couch or even off the Corridor trails for that matter. Off-trail hiking in the Grand Canyon is unique to the Grand Canyon and it requires a honed set of skills including hiking, climbing, canyoneering, and navigational expertise (Rudow, 2016).

A recent survey of AT thru-hikers revealed that 87 percent forego carrying a map and opt instead to bring along a guidebook. That sounds crazy, but given that the AT is marked by 165,000 white blazes, which averages out to about one white blaze every 70 feet, it might be easier to get lost on the Bright Angel Trail than on the Appalachian Trail. If you were to get lost on the AT or if you were to have a catastrophic equipment failure - have no fear! Roads cross the trail on average every four miles and the nearest town where you can buy replacement gear is never that far away (REI Blog, 2016).

Hiking the length of the Grand Canyon without a map? Bad idea. Really bad idea. Buying a guidebook for hiking the length of the canyon? It doesn’t exist. So where do you start? The first thing we did was to narrow things down by setting the terms and conditions for our hike. We agreed that we wanted to hike entirely below the rim on the north side of the Colorado River moving upstream from Pearce Ferry to Lees Ferry. From there we proceeded to develop our route.

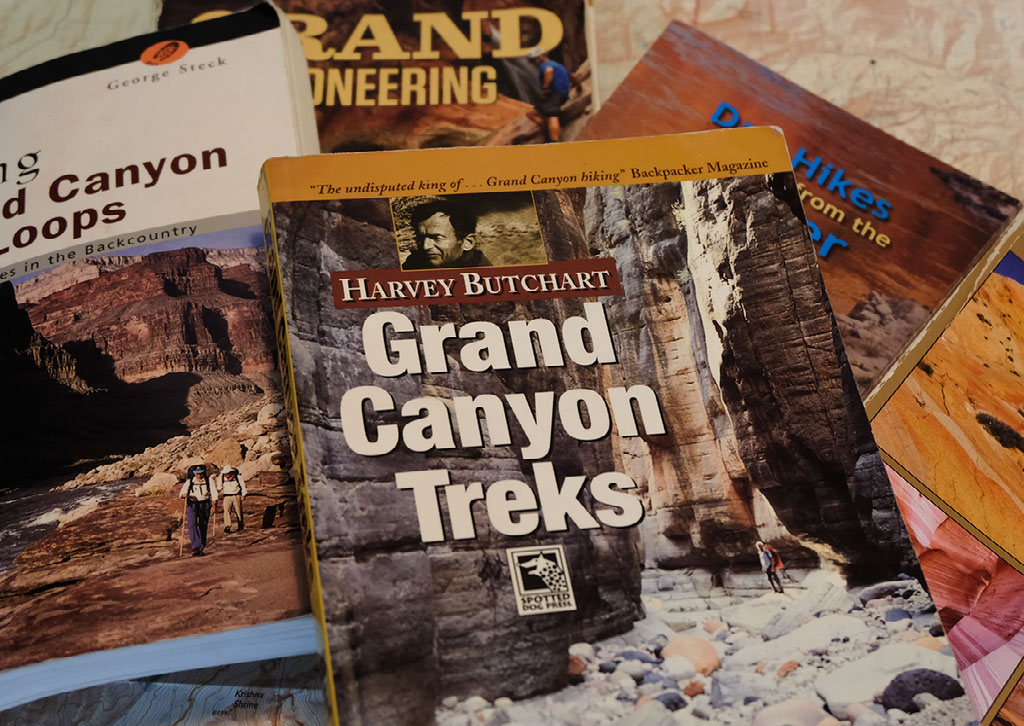

Without an established trail or route through the canyon, and without an official guidebook, the determined hiker must put together route options from a variety of incomplete sources (Rudow). As a result, every individual or group that has hiked the length of the canyon has done so in a unique way. When developing our route, we took into account all of the firsthand knowledge that we had gained during the years we have lived and worked at Grand Canyon; we closely examined maps on many different scales; we sifted through every guidebook ever published about Grand Canyon hiking; we meticulously read through the trip reports, logs, and journals of legendary canyon hikers; and, we sought out living canyon experts in order to ask them questions and listen to their stories.

The extended research that went into developing our route revealed that the history of the Grand Canyon thru-hike is one filled with a colorful cast of characters, each of which despite trial and tribulation held an unwavering devotion to the Grand Canyon. After many months, our route began to take shape, as we carefully drew our line contouring up and down amongst the canyon walls. Far more than just a line, our route was made of stories. We would carry our maps and the stories of Grand Canyon’s legendary hikers with us for the next month and a half as we sought our own adventures.

PEARCE FERRY

On December 11th, two friends graciously drove us from the South Rim to Pearce Ferry where we would use packrafts to cross the Colorado River and then begin our walk. It is often said that there are two easy ways to die in the desert: thirst and drowning. On the first day of our journey, either of those seemed possible. While the water at the Pearce Ferry boat ramp is flat, it was impossible to ignore the roar of the Class VI (un-runnable) Pearce Rapid only a quarter-mile downstream. While this rapid has been shaped in the past few years by the retreating water-levels of Lake Mead, the landscape surrounding the river channel has also significantly changed as the result of prolonged regional drought.

After safely crossing the river, we trudged through sandy soils and thrashed through a forest of non-native tamarisk, all land that was once under the water of Lake Mead. Covered in creosotebush (Larrea tridentata var. tridentata), the hillsides above the old lakebed served as a reminder that the western Grand Canyon lies on the eastern edge of the Mojave Desert. In this region, only after it rains, does water collect into a few known pockets that lie tucked away in the shady and remote reaches of its canyons. After saying goodbye to our friends, we turned our backs to the Colorado River and headed up Pearce Canyon towards the Grand Wash Cliffs with a crushing 22 pounds of water and 35 pounds of food split between our two packs.

We hiked until dark. Having noticed some storm clouds brewing over the mountains near Las Vegas that afternoon, we set up our first camp on a ledge above the bed of the large drainage. Not even five minutes after we set up our shelter, without even a sprinkle, it started pouring rain and did so on and off throughout the night. Typically, a rainy start to a backpacking trip can lower morale. However, heavy rain on the first night of a backpacking trip in which you are about to spend days walking across one of the driest sections of the Grand Canyon was a gift. The next morning there were potholes filled with clear rainwater all of the way up Pearce Canyon, and as we scrambled up and onto the vast Sanup Plateau we could see fresh snow dusting the rim of the Shivwits Plateau 1,000 feet above us.

ROUTES

I mentioned earlier that our route through the canyon was made up of stories. First and foremost our maps captured stories of water. These stories translated to more than 300 waypoints, some marking mythical potholes the size of swimming pools, some marking potholes that if present would likely be so thin that we would need to carry a ziplock bag in order to skim the precious liquid from the slight depression in the surface of the rock.

In some parts of the canyon, the waypoints were spread over a day’s walk away from each other. In these parts of the canyon water is so rare that the few places it is consistently found, people have been visiting for hundreds if not thousands of years.

Second, the line on our map told stories of the possibility for safe passage through seemingly impenetrable terrain. These possibilities are what we call routes. "They are threads streaking through cliffs and inner grottoes, days of narrow shelves and bridges built of fallen boulders. Traveling along these routes is like studying the skeleton of an animal, the way joints hinge off of each other. But they are not easy to find. The Grand Canyon is a lesson in riddles, a 2,000 square-mile conundrum of stone where only certain ledges or crevices connect one place to the next, and the rest, most of it, is a dead end, a land of cliffs" (Childs, 2003).

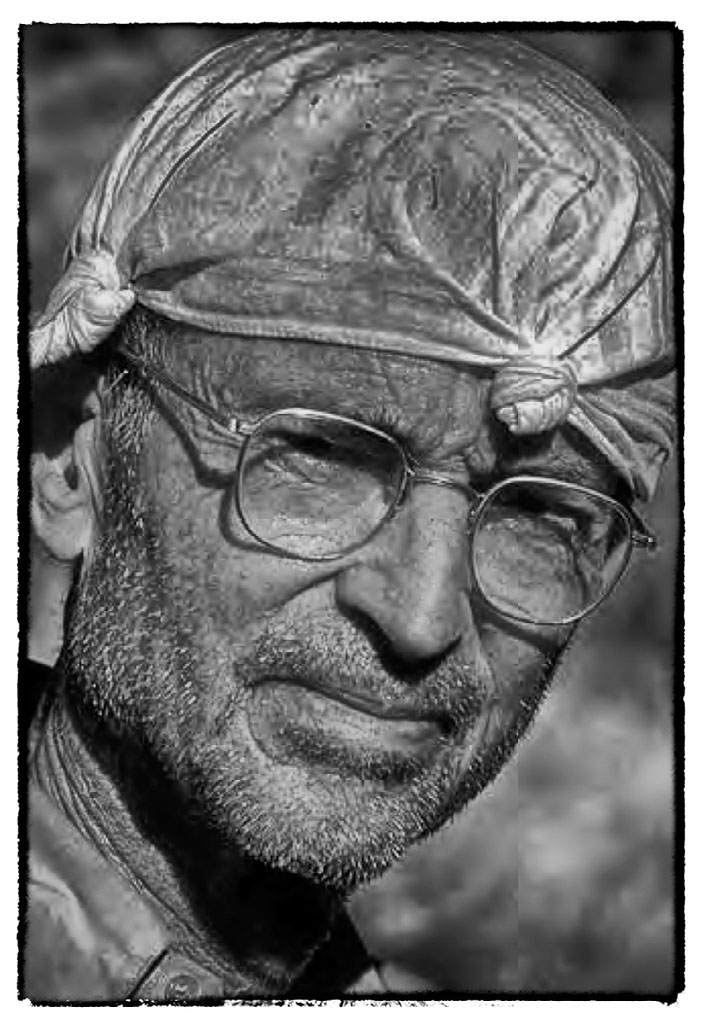

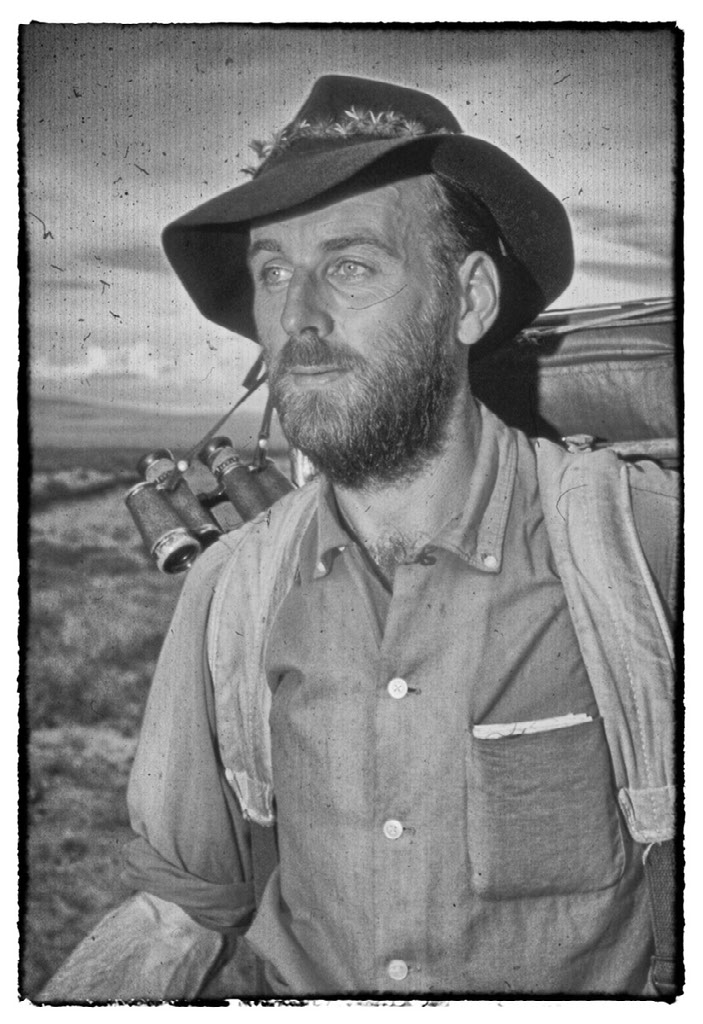

HARVEY BUTCHART (1907-2002)

When it comes to knowledge of routes and experience in Grand Canyon’s backcountry, there is one man that stands above all others. The undisputed king of Grand Canyon hiking, Harvey Butchart. In 1945, Harvey was 38 years old when he moved with his family to Flagstaff where he had accepted a position as math professor at Arizona State College. Over Thanksgiving break of that year, he went for his first hike in the Grand Canyon. He hiked down the South Kaibab Trail to Phantom Ranch and back up to the South Rim on the Bright Angel Trail all in one day. In May 1987, at age 80 he hiked from the Sanup Plateau near Surprise Canyon up to the rim one last time.

In the 42 years between his first and last hike, Harvey spent 1,021 days in the Grand Canyon. He had embarked upon a whopping 560 trips, all of which were executed over his weekends and regularly scheduled breaks from teaching. In total he rambled 12,000-miles below the rim; he ascended 83 inner canyon summits; he documented 164 places where he had been through the Redwall limestone; and he completed 116 different rim-to-river routes. While Harvey’s hiking accomplishments remain astounding, his legacy does not stop there. He was the first person to write guidebooks about backcountry hiking in Grand Canyon (Grand Canyon Treks I, II, and III) and he donated a treasure trove of information to Northern Arizona University's Cline Library, which included: over 1,000 pages of logbook entries, thousands more pages in written correspondence, and over 7,000 photographic slides of the canyon (Butler & Myers, 2007).

Despite his accomplishments, Harvey felt that he had left behind plenty that was undone. In an interview he said that the two things he regretted having not done in the canyon before he was sidelined with a bad hip were to finish section-hiking the length of the canyon on the north side of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to the Grand Wash Cliffs and to connect a route through the Redwall from Nielson Spring on the Sanup Plateau to the bed of Surprise Canyon (Quinn, 1994). When writing about Surprise Canyon in his book Grand Canyon Treks (1998), his two regrets are synthesized into one simple sentence and weighted with the unprecedented use of an exclamation mark.

It would be an exciting part of a through-canyon route!

SURPRISE CANYON

A few days into our hike, we stopped for the night about a mile from Nielson Spring where we fell asleep under a clear sky and woke up the next morning to see the entire Sanup Plateau blanketed in three inches of snow.

We had made plans with two friends to check-in via text message twice a week. Turning on the satellite phone that morning and sending our scheduled check-in text, we immediately got a message back from one of them suggesting that we either take advantage of a pocket of fair weather that would likely last until afternoon and stay on itinerary to descend through the Redwall to the bed of Surprise Canyon; or, we take a two-day detour and contour on the Sanup all of the way around to the head of Surprise Canyon in order to avoid what could be an increasingly wet and icy Redwall descent.

We quickly packed up our gear and we decided that we were going to give it a shot. Having come up this Redwall route on a previous trip, Matt felt confident that we would be capable of completing it as long as the weather conditions didn’t deteriorate any further. We carefully started making our way down the upper arms of the drainage passing Nielson Spring. The clouds were spitting snice, the rock was wet and slick, but manageable. After a couple of hours we had rounded a promontory and we were on top of the Redwall limestone. Beams of sunlight were breaking through the clouds and we had a view all the way to the floor of Surprise Canyon. From where we stood it appeared to be a sheer drop. Never, in any part of the Grand Canyon had I seen the Redwall limestone this thick and terrifying.

This was it, this was the first major crux of our trip. We would have to complete two climbs, neither of which could be made that much safer through the use of a belay. The first climb we would have to use hand and footholds to descend straight down a 40 foot cliff and the second would require a diagonal traverse 35 feet downwards across a face. As Matt nimbly completed the first climb, I took deep breaths and thought back to a morning in September when the two of us had hiked from Indian Garden to the top of the Battleship. When we got to the top we were perusing the summit register, where the most recent person to sign it had also left a quote by Harvey Butchart.

You aren't really living if you don't risk your life once every six months.

Crouched at the top of the Redwall, looking into Surprise Canyon I wondered if professor Butchart might award me some extra credit points for this one. As Harvey predicted, this Redwall descent was certainly proving to be "an exciting part of a through-canyon route," and as he told Michael Quinn in an interview, it was no doubt “one of the most interesting routes of all." After climbing and scrambling our way down a wet mossy chute, our feet hit the bed of Surprise Canyon about an hour before dark and we both sighed a breath of relief.

In his late sixties and seventies, Harvey began spending much of his time in the remote western Grand Canyon. There were likely several reasons why he gravitated to this overlooked area of the national park, one being that water levels were high enough that he could access tributaries such as Burnt, Separation, and Surprise Canyons from their mouths by boating upstream from Lake Mead. Without having to descend first on foot, or make a taxing return hike to the rim, he could save his limited energy for route finding from the side canyons’ lower ends. In these years, Surprise Canyon became a favorite haunt of his (Butler & Myers). When asked if there was ever a place in the Grand Canyon where he felt a perfect sense of wilderness or serenity, Harvey said it was in Surprise Canyon (Quinn).

WILDERNESS

The western Grand Canyon constitutes one of the most remote regions in the lower 48 states and the sense of wilderness in this section of the canyon is unparalleled. When designing our thru-canyon route one of our goals was to experience this wilderness to the greatest extent possible. The first decision we made was to hike upstream from Pearce Ferry to Lees Ferry. We chose to hike in that direction, because we wanted our canyon traverse to be distinctly different from the experience one might have when taking a Colorado River trip. Some people might ask, why bother to hike the length of the canyon when you can sit on a boat and take it all in with a beer in your hand? Well, although you can travel the length of the canyon at the river-level on a boat, hundreds of thousands of acres of Grand Canyon National Park remain out of view and out of reach when you are tucked in amidst the soaring walls of the inner gorge.

Descending to the mouth of Surprise Canyon, we then followed the faint tracks of bighorn sheep for about eight river-miles, threading our way in and out of a series of steep bays suspended above the lower granite gorge. While it would have been possible to continue walking upstream directly above or near the river-level for at least another 70 river-miles, when we arrived near the mouth of Separation Canyon we turned left and headed back up towards the Sanup Plateau.

It is impossible to hike up Separation Canyon without recalling the story from which this gigantic tributary got its name. It was here on August 28th, 1869 that William H. Dunn, Oramel G. Howland, and his half-brother Seneca Howland separated from John Wesley Powell’s Colorado River expedition. Festering disagreements with Powell, a near starvation diet, and what they perceived to be as the worst rapid of the expedition may have contributed to their decision to leave. The men hiked up Separation Canyon and were never seen again (Brian, 2015).

From the wide gravelly bed of lower Separation you can see all the way up to the Kaibab limestone rim of the Shivwits Plateau. Passage through the Redwall limestone in the eastern arm of the canyon was nowhere near as strenuous as Surprise Canyon, but it was instead characterized by the tight turns of a silvery polished slot canyon. Emerging onto the Sanup Plateau, Powell’s men must have felt that the Shivwits rim and civilization were so close. Yet even today, the tip of Kelly Point lies approximately 120-miles from the paved roads of St. George, Utah.

CACHES

As dusk was quickly turning to darkness, we re-emerged on the Sanup and Matt started skipping towards a large juniper tree. Why the enthusiasm at the end of a long day of hiking? Buried beneath a pile of rocks and duff at the base of that juniper tree was our first of nine caches. It contained food, fuel, and most importantly a package of gummy bears.

We knew that there was no way we could carry a month and a half of food with us through the canyon and we had agreed that our hike would stay entirely below the rim. Therefore, we spent the late summer planning and taste-testing meals, purchasing ingredients, and packaging our food. Lucky for me, Matt has a black belt in Microsoft Excel.

By October our buckets were packed and it was time to start putting them in place before winter storms would make the North Rim roads impassable. Our cache trips consumed all of our weekends and annual vacation time. Placing these two buckets under this nondescript juniper tree perched along the rocky windswept ridge of the Sanup Plateau resulted in a mini-epic requiring a combination of jeeping, bikepacking, and hiking.

Our cache was placed in this spot because we planned to walk around the Kelly Point promontory at the level of the Sanup Plateau. This vast track of land that lies miles away from the river and a 1,000 feet below the rim, may be the least visited and wildest tract of land in Grand Canyon National Park. Only a handful of people are known to have traversed this terrain due to its remote access and utter lack of water. As we set up camp in the lingering snow near that juniper tree, temperatures quickly began to drop. It would be the coldest night of our entire trip with the temperature dipping into the single digits. Needless to say the gummy bears were frozen.

The next few days hiking below Kelly Point consisted of sunny afternoons that melted the remaining snow into potholes and cold nights with camps perched on the slick-rock benches overlooking the rarely visited canyons south of the Colorado River. These canyons have largely remained unexplored by recreational hikers as the land on the south side of the Colorado River in the lower 100 river-miles is managed by the Hualapai tribe.

ESPLANADE

When you walk, you have time to pay attention to your surroundings.

Hiking below Kelly Point we had grown accustomed to its snowy north-facing bays as well as the ancient flows of basalt cascading off of Price Point. Then, we found ourselves on top a of swale and in an instant our entire viewshed changed.

Laid out before us were the next few days of our walk, with the Uinkaret Mountains in the far distance. Having arrived at the eastern edge of the Sanup Plateau, we would continue traveling on what is commonly referred to as the Esplanade. Where as the Indian Garden area is characterized by the Tonto platform and its broad bench of eroded Bright Angel shale, the western two-thirds of Grand Canyon is characterized by the Esplanade sandstone. Canyon surveyor Clarence Dutton dubbed this seemingly smooth rock platform the Esplanade in 1882, likening it to a public walkway of the same name in New York City’s Central Park. The word Esplanade is derived from two Latin words meaning a level space used for public walks and drives, or an open level space between a fortress and a town (McNamee, 2004).

Not quite a fortress and not exactly a town, we were headed across the Esplanade towards the Greater Tuweep Metropolitan Area. Located just on the other side of the Uinkaret Mountains lies Grand Canyon’s most remote ranger station. Situated in the broad Toroweap valley, the Tuweep ranger station and its nearby campground are located over 60-miles down a rough dirt road from Fredonia.

As we made our way towards Tuweep, a winter storm system moved into the region making for constantly shifting light and especially dramatic sunsets. The winter solstice came and went; and, we continued to hike all day everyday with the exception of a lunch break. Short days made for long nights. One of my favorite aspects of winter backpacking is that you can completely wear yourself out hiking all day and then you have more than enough hours to rest and recharge your battery for the next day.

On our 12th day of hiking, we had walked ourselves into the middle of the storm that had been moving around us for days. Crossing over the Uinkaret Mountains we got pummeled by rain blowing sideways, snow, and deep mud. Descending into the Toroweap Valley, we were welcomed by bold rays of sunlight and a double rainbow. Soaking wet and smelling absolutely wretched, our arrival at Tuweep marked the completion of the first third of our journey and it would be the first time that we had seen, let alone spoken with, any other people since leaving our friends at Pearce Ferry.

We took a rest day at Tuweep where we had placed our third cache. We ate gummy bears and enjoyed the company of the NPS ranger and volunteer on duty, as well as the three guests that had come out to visit them for the Christmas holiday. During our rest day at Tuweep we got around to talking about the history of long walks in the canyon. While many people are aware that John Wesley Powell and his men were the first recorded European-Americans to traverse the length of the Grand Canyon by boat, do you know who the first recorded people to walk the length of the Grand Canyon were?

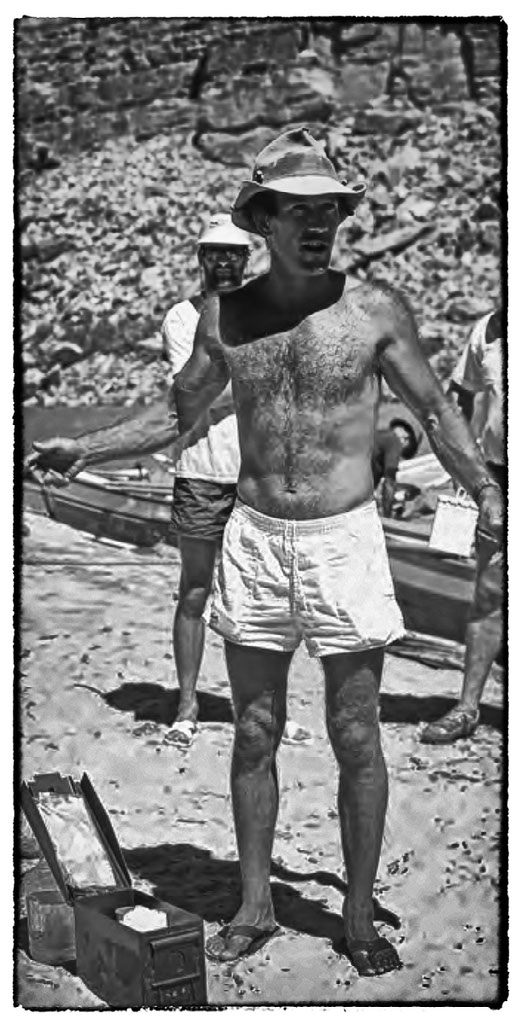

KENTON GRUA (1950-2002)

Kenton "Factor" Grua, was the first person in recorded history to walk the length of the Grand Canyon and he did so entirely on the south side of the Colorado River. His friends nicknamed him, "Factor," because he was this additional element you always had to factor in whenever you were on a river trip, or in the warehouse, or anywhere with him... frequently brilliant, sometimes insane, usually intense... always a factor (Steiger, 1997).

He first had the idea to do this hike in the late 1960’s after reading Colin Fletcher’s best-seller The Man Who Walked Through Time: The Story of the First Trip Afoot Through the Grand Canyon (1968). Grua said that while he found Fletcher’s book interesting,

Anyone who knew the canyon could see right away, that he didn’t really walk through the whole Grand Canyon.

This is true. In 1963, Fletcher was the first person to continuously walk the length of the canyon within what are now the old boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park. When Fletcher conducted his trip the boundaries of the national park did not include the entire geophysical length of the Grand Canyon. In other words, the boundaries of the park did not include the 52 river-miles upstream from Nankoweap known as Marble Canyon and the 143 river-miles downstream from Tapeats Creek. While Fletcher’s journey covered an impressive 104 river-miles (250 foot-miles), he would have had to walk an additional 400-miles to have hiked the geophysical length of the gorge (Butler & Myers). In an interview Grua said,

I thought somebody else needs to do it, just to do it, and do it right, do it light, and do the whole thing.

While working as a river guide in the canyon, Grua scouted potential routes that could be pieced together during his thru-hike. Self-admittedly, Grua was kind of a hippie in those days. He said that he did most of his boating and hiking barefoot, because they didn’t have good flip-flops back then (Steiger). As a result, he decided that he was going to hike the canyon in moccasins. Departing Lees Ferry in the autumn of 1972, wearing his moccasins, it was a mere eight days before Grua aborted his mission because of a foot infection caused by a puncture from a cactus spine that resulted from holes in the bottom of his moccasins (Myers).

Four years later in February 1976, wearing J.C. Penney work boots that were similar to those of his hiking mentor Harvey Butchart, Grua began his second attempt at hiking the length of the canyon on the south side (Myers). At only 25 years old, Grua was young and spry. He found the most difficult stretches to be in the ledges of the Muav Gorge downstream from Havasu. He credits his success in this section to his convincing impersonation of a bighorn sheep. As a river guide he had witnessed bighorn sheep cruising along the very edge of the crumbly Muav ledges that are suspended 100-150 feet above the river. Whenever there was a gap in the ledge system, whether it be four, five, or even six feet, the sheep would jump over the gap and just keep cruising along. Not being a sheep, Grua said that it was pretty hairball. "You’d get sort of wigged out, and then climb up and go along in the boulders for a while, until it felt like it was safer, but scrambling amidst the boulders was excruciatingly slow... so you’d come back down to the ledges and just start moving and making the jumps" (Steiger).

Kenton Grua would complete his trek at the Grand Wash Cliffs after just 36 days of walking. As a side note, Grua was not only a “factor” on land, but also on water. In 1983, with a lot of help from a surging river, Grua, Rudi Petschek, and Steve Reynolds somehow managed to row Grua's wooden dory the Emerald Mile from Lees Ferry to the Grand Wash Cliffs in only 36 hours, 38 minutes and 29 seconds, breaking the previous record of just under 48 hours that Grua had helped set three years earlier (Fedarko, 2013).

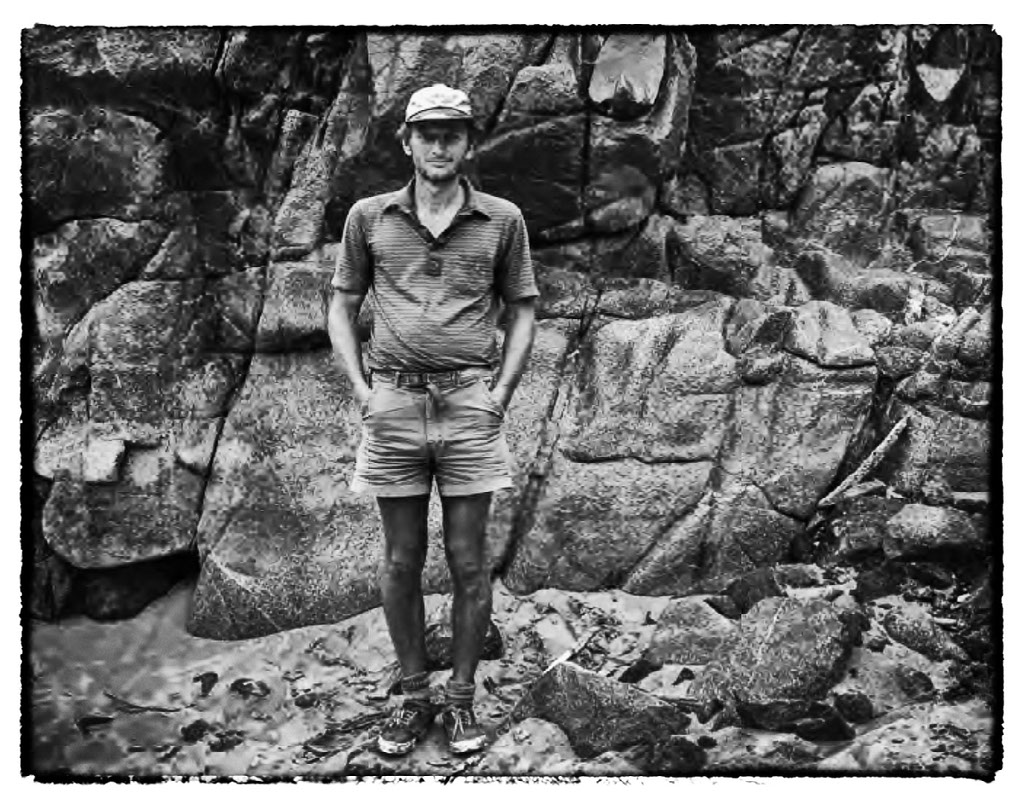

BILL OTT (1947-)

While it is not possible to hike the entire length of the Grand Canyon on the south side and stay within the boundaries of the national park, it did become possible to do so on the north side of the Colorado River following the passage of the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act of 1975 (Public Law 93-620). Through an act of Congress, the size of the national park was doubled to include Marble Canyon upstream and the length of the canyon downstream of Tapeats Creek to the Grand Wash Cliffs. It was in 1981, that 35 year old Grand Canyon river guide and future Dinosaur National Monument river ranger Bill Ott became the first person to complete a north side traverse. He hiked for 78 days, during which he had to exit the canyon briefly at Kanab Creek for resupply after he found his cache had been stolen (Myers).

Ott lived in Arizona for many years before moving to a rural community in southern Oregon, where he built a log cabin by hand without using any power tools. Annually, Ott would return to northern Arizona to do a long hike in the Grand Canyon. In the spring of 2012, at age 65, Ott left his vehicle at a friend’s house in Flagstaff and he took a ride out to Mohawk Canyon, a remote area on the Hualapai reservation which is located across the river and a few miles upstream from Tuweep. He was starting a 21 day backpacking trip and his plan was to hitchhike back to Flagstaff when he finished. Despite an extensive search of the region by foot and by air, the last time Ott was seen was on April 5, 2012, the day he was dropped off near Mohawk Canyon (Cole, 2012).

TUCKUP

We walked away from Tuweep on December 24th knowing that the next time we would be seen would likely be at Phantom Ranch in about two and a half weeks. As we veered onto the Tuckup Trail, we followed an old road bed for three miles until it gave way to a wonderland of sandstone ledges and canyons. While hiking the Esplanade on the opposite side of the river in 1963, Colin Fletcher, aptly described the geologic character of this portion of the canyon (Fletcher, 1968). He wrote that the apparently flat Esplanade imposed a consistently serpentine route.

Every step was a zig or zag: zig along a sidecanyon; zig again for a side-sidecanyon; then zag along its far side for a new side-sidecanyon; and then another zig up a side-side-sidecanyon. And the going was almost never level.

In spite of all of the zigging and zagging, the storm system that had entered the region about a week earlier persisted and continued to put on an ever-changing show of shifting light and moving clouds.

The storm, not quite finished, battered our shelter all night long with huge gusts of wind.

Groggy from a lack of sleep, we unzipped our shelter on Christmas morning to see the Esplanade covered in pools and snow. We felt as though we’d won the lottery. A white Christmas on the Esplanade, unbelievable! Once again, we had received the greatest gift of all... water.

By midday the storm was breaking up, and as the sun appeared the snow quickly began to melt.

I thought of Clarence Dutton. Remember, the man that named the Esplanade? In his classic text, Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District (1882), he wrote of the area:

We find its surface to be mostly bare rock, with broad shallow basins etched into them, which hold water after the showers. There are thousands of these pools, and when the showers have passed they gleam and glitter in the sun like innumerable mirrors.

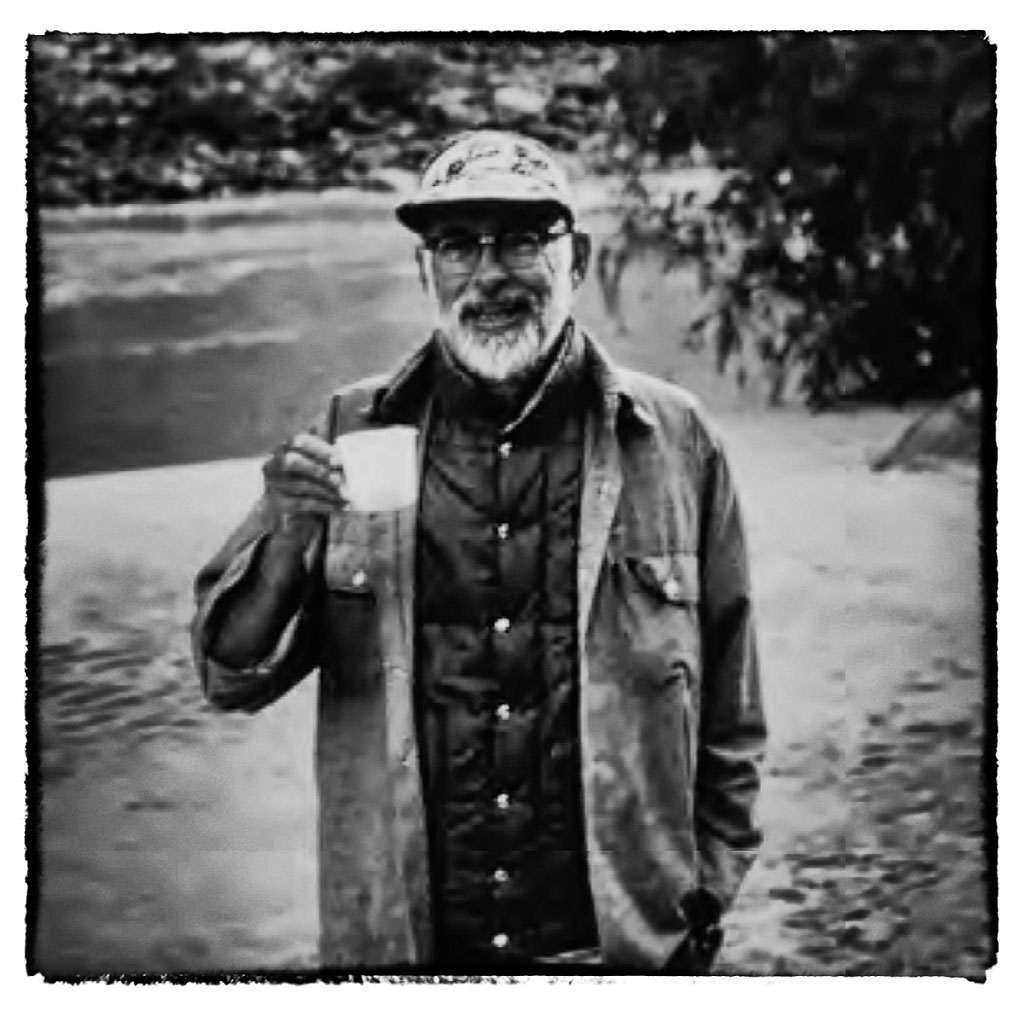

GEORGE STECK (1925-2004)

At Tuweep we had exchanged the pages of Harvey Butchart’s logs that we’d carried with us from Pearce Ferry with photocopied pages from George Steck’s book Hiking Grand Canyon Loops: Adventures in the Backcountry (2002). While Butchart’s guidebook and logs were the most comprehensive resource available for understanding the western Grand Canyon, Steck’s book would be our primary source of reference for the central Grand Canyon. In an essay written about Steck (Banks & Childs, 1999), author Craig Childs states:

I don’t know what should be told of George Steck first – that he pioneered routes in the Grand Canyon or that he has a Ph.D. in statistics from Berkeley.

Interesting. Is it merely a coincidence that George Steck and Harvey Butchart, both pioneering route finders in the Grand Canyon, each held a Ph.D. in mathematics? In his writings, Childs ponders the following questions: Is it that navigating a complicated strand of logic is in fact similar to working through unknown routes in the Grand Canyon? Is it that there are proofs and theorems with every step; givens in certain rock formations; logarithms carved out of canyon floors; sums and solutions in arriving at the other end?

When Childs asked Harvey about a connection between route finding and math, apparently Harvey waved away the question as if it had a foul smell. Harvey said, "Math is math, route finding is route finding." Steck on the other hand told Childs, "The confidential language of logic is much like our negotiation of difficult terrain, the way our eyes find ways through what other people might see as dead ends."

According to Childs, George Steck claimed two great epiphanies in his life. The first came from his work at the Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, where he made a mathematical discovery of epic proportions proving a series of unconfirmed theorems. When speaking of his work in mathematics he said,

Ultimately I found a very simple, beautiful formula for some very complicated expressions.

In essence, Harvey was a vertical route finder, devoting a good portion of his life to looking for ways to get up and down through the Redwall. Being of the next generation of Grand Canyon hikers, Steck, took Harvey’s hard-earned routes and carefully sewed them together creating a series of loop hikes that are uniquely described in his book (Banks & Childs).

Where as one of the most exciting moments in Harvey’s Grand Canyon Treks (1998) is his use of an exclamation mark in reference to the Redwall route in Surprise Canyon; Steck’s book tells you not only of where he has found off-trail possibilities, but he also gives you tidbits such as how to get beer from a passing river trip, how to walk with only one boot, and a recipe for pasta with corned beef and barbecue sauce that will feed eight (Steck, 2002). If you are looking for a simple guidebook that tells you how to get from A to B, Steck’s book isn’t it. I consider the first 50 pages of Hiking Grand Canyon Loops, to be 50 of the best pages ever written about hiking in the Grand Canyon. Take the section “How to Use This Guide,” which starts with a quote from none other than Long John Silver.

Them that die’ll be the lucky ones.

Now that's an interesting way to start a guidebook about hiking in the Grand Canyon! Steck had a sense of humor. Yet, his writing should never be taken as small talk or as an open invitation to walk in the canyon. Steck’s book does not give you coordinates to punch into your GPS, rather it gives you just enough to get out there and then figure it out for yourself, with the understanding that it is not going to be easy. In his introduction, he states, "The purpose of this book is to facilitate, not to discourage. I have the same purpose in writing it as Goossen did in writing the book with the intriguing title Navajo Made Easier (1967) – I want to make it easier for hikers to enjoy the Grand Canyon outback. However, I have the same problem Goossen had: I cannot make it easy."

Steck’s second epiphany did not come easy. Pioneering a route up 150-Mile Canyon, east of Tuweep, he inched his way over choked boulders through the cavernous narrows of the Redwall limestone as drizzle turned to rain. He emerged on the Esplanade with his brother Allen, his son Stan, and their friend Robert, only a couple of hours before a flash-flood arrived. This happened in October 1982, amidst an 80 day expedition from Lees Ferry to the Grand Wash Cliffs. Whereas Harvey’s hiking career consisted of weekends and school holidays. George Steck would spend four weeks a year exploring Grand Canyon. In the spring and fall he would take one week exploratory trips and each summer he would spend two weeks hiking in the canyon with family and friends. At age 57, Steck's 1982 north side thru-hike was the culmination of all his previous adventures, piecing together sections of his loops into one long line.

While our route was not going to take us through the Redwall narrows of Steck’s second epiphany, we did opt to hard-cut our way across 150-Mile Canyon. I use the term hard-cut, because although choosing to cut across a canyon, may in fact be shorter than contouring around to the head of a canyon, you are often mistaken if you expect it to be easier. Steck is right. Steck is always right. In the introduction of his book, he explains that the psychological difficulties attending Grand Canyon hiking are at least as important as the physical ones, and our enjoyment of a hike can be strongly influenced by what we expect it to be.

If reality roughly conforms to our expectations, then we are happy campers. If not, we’re not.

By this point, Matt and I had come to the conclusion, there are no short-cuts in Grand Canyon, only hard-cuts. When determining how we would negotiate the Kanab Creek drainage, we pondered hard-cuts and what I like to refer to as long-cuts.

KANAB CREEK

The Kanab Creek drainage is gigantic. The creek itself flows south 50-miles before it drains into the Colorado River. Approaching Kanab Creek from the west at the elevation of the Esplanade we had to determine which tributary or sidecanyon of Kanab Creek we would use to descend into the main drainage. For us, the shortest way into Kanab would have been a semi-technical hard-cut likely requiring the use of a rope and swimming through deep potholes. While swimming through a pothole often sounds delightful in June, without carrying extra gear in the middle of winter you risk hypothermia. Not wanting to add any extra pounds to our packs, we opted to contour for an additional day to a non-technical tributary called Flipoff Canyon.

Having spent the past week hiking primarily on the Esplanade where the most abundant water was found in potholes, Kanab Creek was a Shangri-La of emerald pools, dripping springs, and whispering waterfalls. The sound and smell of water replaced the windswept Esplanade. Boulder-hopping for miles in an attempt to keep our feet dry, we arrived at the mouth of Kanab Creek on New Year’s Eve. It was the first time that we had been at the river-level in the three weeks since we left Pearce Ferry.

My all-time favorite way to celebrate New Year’s is to wake up in a national park and go for a hike at dawn before the rest of the world is up. Waking up at the mouth of Kanab Creek was unforgettable, because it not only marked the New Year, but at river-mile 144 it meant that we had walked half the length of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon.

POWELL PLATEAU

From Kanab Creek, we hiked along the river over to Deer Creek where we would camp for two nights. Having hiked eight days straight, we decided to spend a sunny day patching and sewing holes in our gear on the patio above the Deer Creek narrows. With a new cache of food in our packs, we would cross Surprise Valley to see Thunder River. Only a half-mile in length and plummeting over 1,200 feet it is one of the shortest and steepest named-rivers in the world. From Thunder River, we hiked along Tapeats Creek towards the Colorado River and followed Steck’s low-route around Powell Plateau.

George Steck said, "Great loops are born of great promontories. Loops are constructed by finding connections between nearby drainages, and the farther apart the mouths of these drainages are, the more magnificent the loop."

In 1981, Steck, pioneered a loop hike that drops off the North Rim near Swamp Point and descends 800 feet in elevation to a spot called Muav Saddle. From there, it plunges through the Redwall narrows of Saddle Canyon to Tapeats Creek, around Powell Plateau, up the North Bass Trail from Shinumo Creek to Muav Saddle, and returns to the rim at Swamp Point. Knowing that the Muav Saddle is way up around 6,700 feet and that we would be passing through this area in early January, our plan was to take the low portion of Steck’s loop to avoid treacherous ice and snow that would likely be present at the higher elevations. Matt had told me stories of crawling through snow and sleeping soaking wet in single digit temperatures on a previous winter trip up and over Muav Saddle. This was an experience that he wasn’t interested in repeating.

Walking around Powell Plateau, rather then cutting it off at the Muav Saddle was yet another long-cut that would add at least an extra day to our itinerary, but similar to contouring the Sanup below Kelly Point, the route around Powell Plateau is one that is very rarely traveled on foot. This route provided us with unrestricted access to pockets of the canyon that are typically only accessible via river travel or by desert bighorn sheep.

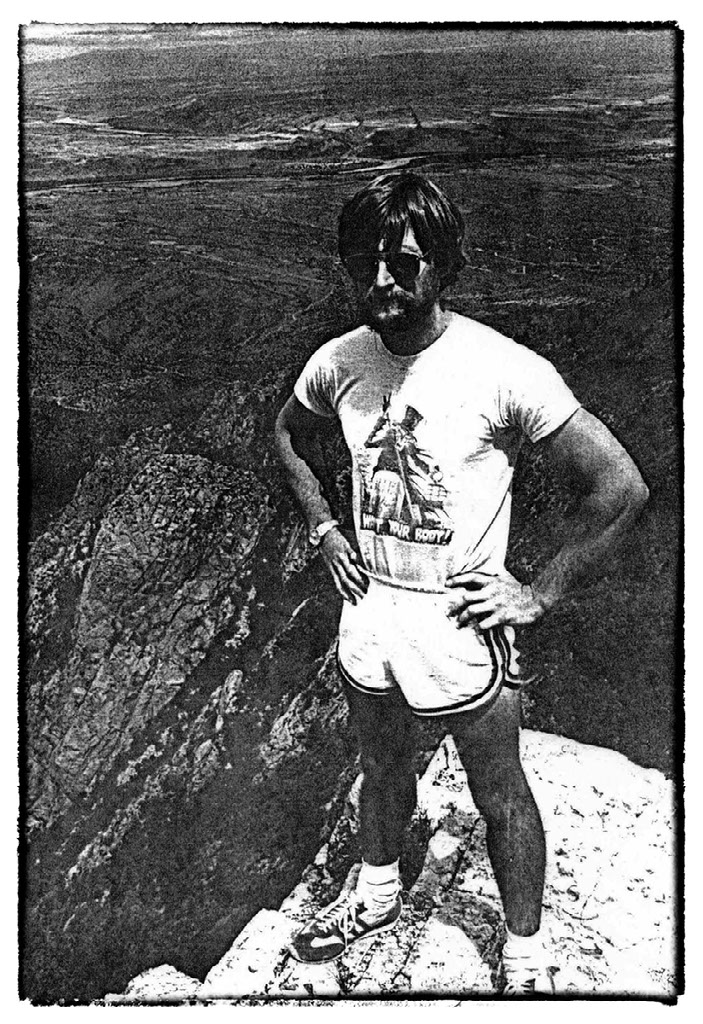

ROBERT BENSON ESCHKA (1956-1984)

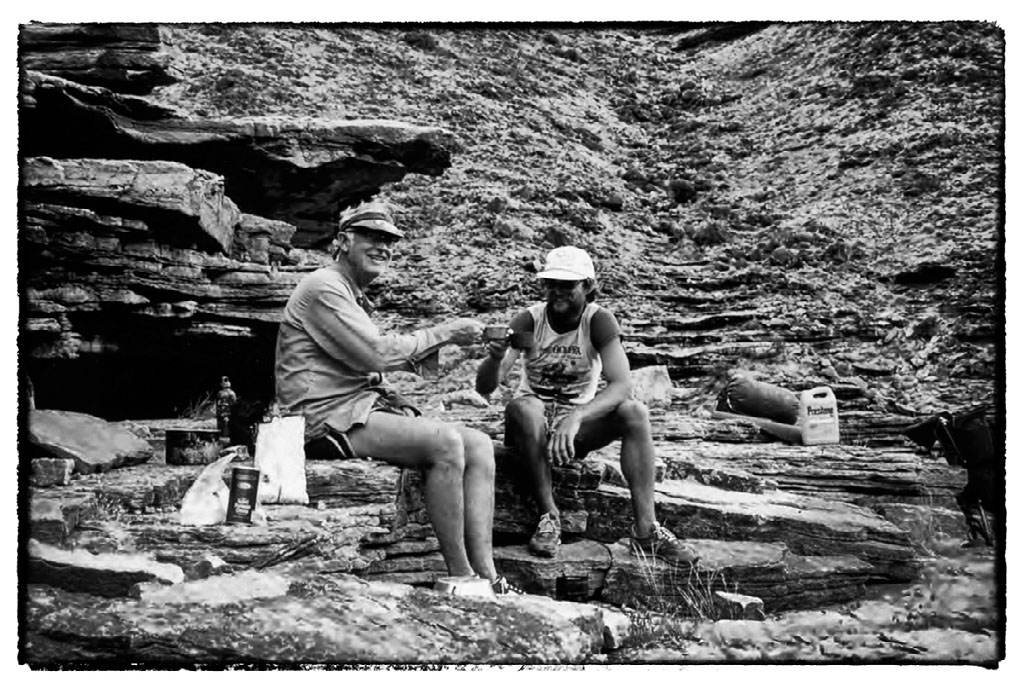

Steck pioneered the route below Powell Plateau in the autumn of 1981 on one of the many exploratory backpacking trips that he took with his long-time friend, Don Mattox. On this trip they invited a recent arrival on the Grand Canyon hiking scene, a 25 year old who went by the name of Robert Benson. Robert had been introduced to them by a friend in Albuquerque. A year later, when Steck and his brother Allen embarked upon their thru-hike of the canyon, Robert would join them on the expedition, although he would be traveling under his own backcountry permit.

During their thru-hike, when they arrived at Shinumo Creek, George and Allen proceeded to follow the route around the base of the Powell Plateau. An enthusiastic route finder, Robert, decided that he would break away from the Stecks for a few days and take the high route so that he could hike to the summit of Elaine Castle. From there, he would scope out potential routes through the Redwall and Supai benches west of Merlin Abyss. Robert’s plan was to meet back up with the Stecks on the west side of Powell Plateau.

After splitting with the Stecks at Shinumo Creek, Robert day-hiked to the summit of Elaine Castle. On October 11th, he wrote in his journal that the view from the summit was spectacular and that the register included the names of only four other parties, one of which was Harvey Butchart 13 years earlier. Descending from the summit, Robert began traversing a crumbly ledge. As he was working along the rock face both handholds suddenly broke free, and he fell backwards over a 30 foot cliff. As he fell, he remembered seeing the bottom getting closer and closed his eyes (Eschka, 1982). In his journal he wrote the following:

Felt impact. No pain. Tumbled and rolled 20 feet, silence! Still no pain, face down, could not believe it happened, must be a dream, opened eyes, saw blood stains on rock, couldn’t move, paralyzed probably from shock, remained there for some time, then slowly got up, could move everything but accompanied with severe pain.

Alone and injured, he faced the added danger of spending a cold night wearing only a t-shirt and running shorts. He needed to get lower. Pain shot through his body each time he tried to stand up, so he crawled. Robert crawled for the next five days in extreme pain, dragging his pack behind him. He followed a rocky, cactus-choked route above Shinumo Creek and eventually intersected the North Bass Trail and was faced with a difficult ascent of 3,200 feet (Thybony, 2012). He wrote in his journal:

I will continue to move as long as I have a breath of life left, as it would be a disgrace to be hauled out by a helicopter.

He pulled himself up the rough, steep trail and reached his goal of the old cabin near Muav Saddle. While convalescing at the cabin for a few days, a ranger appeared and offered to take him to the hospital. The rim was close, but Robert was unwilling to exit the canyon even temporarily. The trip meant too much to him. After some additional rest, he continued on his trek. Forcing himself to keep moving, he was able to catch up with the Stecks around Deer Creek and finished the hike with them at Lake Mead just before Thanksgiving (Thybony, 2007).

Returning to Albuquerque, Robert went to visit the doctor. X-rays revealed a fracture in his pelvis as well as a chip of vertebra floating in the vicinity of his spinal column. To the question of what to do about the fractured pelvis, his physician gave him the advice, “Get in lots of walking.” This was music to Robert’s ears, because he wasn’t done hiking (Shunny, 1987). Remember how I mentioned that Robert thru-hiked the north side of the canyon with the Stecks on his own permit? Well, the reason for this was that hiking the length of the canyon on the north side of the river was only one piece of a much longer journey.

When Robert met up with George and Allen Steck at Lees Ferry in September 1982, he had already been walking for two months having started upstream at Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah. After returning to Albuquerque for a work break of four months, Robert’s plan was to return to Lake Mead and resume his hike, this time traveling upstream along the south side of the river. Starting in March 1983, he would complete his journey five months later in Canyonlands National Park near Moab, Utah. In total, Robert had likely walked over 2,800-miles, becoming the first person to have hiked the length of the Grand Canyon on both sides and completing what is likely the most astounding hiking feat in Southwest canyoneering history (Myers).

One can’t help but wonder, what would drive someone to complete such an enormous undertaking (Ribokas, 2000). In Robert’s case, a clue may exist in his past. Born in Weidenberg, West Germany in 1956, Robert was a bright student in his early childhood. By the time he was 12, he had become an almost failing student. Feeling humiliated by his baffled father, he ran away from home. He told Steck that he went to Paris and lived on the streets, drinking from the gutter and eating out of garbage cans. He soon became so sick that his father was summoned to take him home. His father made him promise that he wouldn’t run away from home again until he was at least 18 years old. The father-son relationship did not improve and Robert left for America not long after his 18th birthday (Shunny). He took the surname Benson from a tombstone somewhere in the midwest.

After hitchhiking back and forth, and up and down the breadth of the country, Robert returned to the desert southwest. He was 20 years old when he discovered the Grand Canyon and dedicated the rest of his life to exploring it and the other canyon country of the southwest. It might be said that Robert was a professional backpacker who took work breaks (Shunny). That is, he worked as a carpenter in Albuquerque until money was sufficient for his next trip. He earned enough to buy a 4WD vehicle and an inflatable boat with a motor and even made up a Social Security number so he could pay taxes (Quinn, 1995). Before he died he spent eight years like this. That is roughly four years of intensive exploration, most of which were solo. The exploratory trip around Powell Plateau in 1981 with Steck and Mattox was his first hiking trip with companions (Steck, 1989).

When Robert was growing up in the 1960s, dyslexia most often went untreated. While he wrote English well and spoke it well, he could not read. Moving to the United States, he learned English by hearing it, not by reading it. He may not have been a good reader of English, but he was an expert reader of maps. He could conjure up for his mind’s eye a very accurate picture of Grand Canyon terrain from the most insignificant ripples in the contours (Steck, 1989). This ability along with a high threshold for risk made him an extraordinary route finder. Robert told Steck when they first met that he did not intend to live past 30 and he was already about 23 at that time. Steck believed that this affected Robert’s hiking. Since he didn’t really care whether he was killed, he often took more risk than even a canyon expert like Steck. In terms of pioneering routes, the payoff was enormous (Quinn, 1995).

According to Steck, Robert had hoped to be the first person to walk the length of the north side of Grand Canyon in 1981, but another friend had talked him into postponing it for a year until he gained more Grand Canyon hiking experience. When Robert found out that Bill Ott hiked the length of the north side in 1981, he was upset that he had taken his friend’s advice and not gone for it. In an attempt to console Robert, Steck suggested that he attempt to become the first person to hike both sides of the canyon, inspiring Robert to tackle the hike he eventually did (Quinn, 1995).

It is possible that Robert took on such a huge undertaking in an attempt to impress his father. By doing this great hike, Robert would show his father that he could accomplish something that other people thought was important and that had value. Unfortunately, while Robert was hiking upstream, his father passed away. Robert learned of this when he returned to Albuquerque, where letters from his mother and brother were waiting for him. Both letters requested that he return to Germany. Wanting to return to Germany, Robert was also aware that he had overstayed his visa and that if he left the United States he would not be able to come back (Quinn, 1995). The thought of not being able to come back to the Grand Canyon, and wanting to go home to help his family, may have posed an irreconcilable conflict leading him to take his own life at age 28 (Ribokas).

Even without a fractured pelvis or broken vertebra, hiking in the Grand Canyon can pose significant physical and psychological challenges. Prior to our trip we talked a lot about what we could expect from the canyon as well as from each other. Remember what Steck said? "If our reality roughly conforms to our expectations, then we are happy campers. If not, we’re not."

NORTH BASS TO PHANTOM RANCH

From each other, we expected nothing but the best EB or expedition behavior. What’s expedition behavior? It is treating each other with respect, sharing tasks around camp, carrying your fair share of the weight, having open conversations about risk, resisting the temptation to play the blame game when things don’t go as you expected, and above all… not whining! In terms of what to expect from the canyon, the main topic was winter weather. We went into the trip with the expectation that we could be hit with winter storms on a daily basis. When planning to be out for a month and a half in the middle of winter, it was not a matter of if we were going to get hit with a big storm, it was a matter of when.

As we left Tapeats Creek and began traversing beneath Powell Plateau the sky had become overcast and by the next day we were grateful that we hadn’t been lured into attempting the hard-cut over the Muav Saddle. Rather, we blissfully long-cut our way around Powell Plateau staying below the clouds that had engulfed the rims and that in total had dropped a couple feet of snow at the higher elevations. Expecting the worst, incessant drizzle and flash flood inducing rains didn’t drag us down.

For a man that spoke so honestly of the challenges of Grand Canyon hiking and the need for realistic expectations, Steck puts forth a great irony to the readers of his guidebook by having chosen the cover photo that he did. If you are unfamiliar with George Steck and his infamous loops, you might pull his book off the shelf in the Indian Garden Visitor Center, glance at the cover, and think to yourself, “Wow, I want to go on that hike!”

After all, the cover contains a lovely photo of a couple of senior citizens casually strolling along flat ledges near the Colorado River on a sunny day. WARNING! Do not judge this book by its cover. The cover of this book does not set forth a realistic expectation of hiking in the Grand Canyon outback. Rather, it depicts only the sweetest of moments that exists after countless hard-cuts and long-cuts. Never really knowing where this cover photo was taken, when we happened upon the spot, with overwhelming enthusiasm I hollered at Matt, “This is it! This is it!! This is THE spot on the cover of the Steck book!!!”

It wasn’t far from that spot on the 25th day of our trip that we encountered the first group of people in the backcountry. It was a private river trip with six people on four small rafts. We were so excited to see them that we smiled and waved from the riverbank. As they floated by one guy asked where we’d come from. I enthusiastically shouted back, “Pearce Ferry!” He must have thought I was lying, because he scoffed, turned his eyes back to the river, and kept rowing.

Making our way around Powell Plateau, we had not only seen our first group of people, but the landscape began to reveal more and more of the human history of the canyon. Hard-cutting across Hakatai Canyon, we came across the tailings from old copper and asbestos mines, as well as a plethora of household items scattered about a nearby prospecting camp. There were faint remnants of a trail that would have been used to reach Shinumo Creek, the next drainage to the east. All of these were artifacts from Grand Canyon’s most prominent early-day explorer, trail-builder, miner, family man, and tourism entrepreneur – William Wallace Bass.

Bass personified that rugged breed that ventured into the unknown to claim a life from the wilderness. In 1884, he set up camp west of today’s South Rim Village, near what is now the top of the South Bass Trail. He lived there or at Bass Camp along Shinumo Creek for the next 40 years. He constructed the first European-American rim-to-rim trail corridor, which he used to bring ore and later tourists in and out of the canyon. For a while he took tourists across the river by boat, but eventually he put in a cable tramway that wasn't cut until 1968 (Steck, 2002).

East of Bass Camp we ascended to the Tonto platform. With the exception of a few hard-cuts across drainages, from there all we would have to do is contour around until we arrived at Phantom Ranch. Contour around. Steck said, "I hate those words: contour around. They are a euphemism for big trouble. Contouring around sounds so easy, yet it is often so hard." Steck is right. Steck is always right. In this case, the big trouble was cactus. Lots and lots and lots of cactus.

It is easy to stand at Plateau Point and imagine how wonderful it would be to meander about the Tonto platform on the other side of the river. However, it is difficult to comprehend how different it is to hike on the Tonto platform sans Tonto Trail. Henceforth we referred to the tedious hours spent tip-toeing through the cactus not as contouring but as tontouring. The proliferation of cactus in this part of the canyon is so notorious that the tributary Tuna Creek is not named after the fish but after the fruit of the abundant prickly pear cactus (McNamee). We celebrated our tontour around Tuna Creek with a snack of tuna, the fish.

After almost a week spent beneath the clouds, the storm system began to break up as we neared Phantom Ranch. Taking advantage of any break in the clouds, we would set out our gear to dry for a few minutes and we would dig into our packs for more snacks. At that point, our appetites were insatiable.

PHANTOM RANCH TO NANKOWEAP

On the 30th day of our trip, we descended from Utah Flats down to Bright Angel Campground in the very last seconds of daylight. We set up our shelter along the creek in site #6. We were ready for a break and excited to have the unprecedented opportunity to play tourists at Phantom. Looking like total dirtbags we weren’t even recognized by the ranch staff for the first 36 hours that we were in the area. We were able to score a reservation for breakfast the next morning as well as the next evening’s stew dinner.

At breakfast, Matt took a seat near the middle of the long table, which worked to his benefit as food passed from both ends of the table would inevitably come to a rest right in front of his plate. We must have eaten 10 pancakes a piece that morning, and when two of the people at our table decided not to eat their chocolate cake at dinner, we made sure that it didn’t go to waste. Phantom Ranch has been hospitable to canyon mule-riders and weary hikers since 1922 and it was a treat to play tourist during one of the quietest weeks of the year down there.

By the time Matt completed his shift as the ranger on duty at Phantom Ranch, we were itching to continue with the last leg of our journey. Hiking about a mile up the North Kaibab, we turned on to the Clear Creek Trail. Built in 1935 by the Civilian Conservation Corps, we appreciated the hard work and craftsmanship that went into the construction of this trail and savored the ease of walking.

After five miles we veered away from the trail and began hard-cutting back down to the river-level and the mouth of Clear Creek. From there we immediately scrambled back to the Tonto platform near to 83-Mile Canyon. Stopping just short of Vishnu Creek, rain fell throughout the night. We couldn’t believe it. We’d gotten rain on the first night of each leg of our hike.

Having hiked from Lees Ferry to Phantom Ranch a few years earlier, one of Matt’s least fond memories of that hike was between Lava and Basalt Canyons, along what is affectionately referred to as “the ball-bearings traverse.” Exactly that, this traverse requires you to pick your way across crumbly, pebble-strewn slopes precariously perched above the void. In order to avoid reliving these memories and passing the trauma on to me, Matt carefully studied the lines drawn on Harvey Butchart’s maps as well as geological maps of the area in an attempt to come up with something better. Ultimately, he devised a long-cut that would include an exciting climb up to Ochoa Point, a long meander back to the head of Lava Creek, and a stroll down the bed of Lava Creek to its intersection with the Butte Fault.

Not only did the route Matt devise take us up and through some extraordinary scenery, but it worked!

In the eastern Grand Canyon, the Colorado River is no longer trapped within the steep schist and granite walls of the inner gorge, but instead the river meanders amongst sweeping and swirling sedimentary Supergroup layers. The landscape is characterized by dramatic faulting and erosion, with one of the largest faults being the Butte Fault which extends from Lava to Nankoweap Creek. The Butte Fault slices its way across a huge promontory of land below the Walhalla Plateau.

Walking the Butte Fault is like being on a roller-coaster, you go from Lava up and over into Carbon, then on to 60-Mile, Awatubi, Malgosa, Kwagunt, and finally Nankoweap.

Each of these canyons consist of different exposures, textures, and kaleidoscopic colors characteristic of the Supergroup.

It is here in this eastern section of the Grand Canyon that one can be immersed in one of the greatest exposures of Supergroup rocks on our planet.

In addition to its geologic significance, the Butte Fault may also have historical significance. The Butte Fault is sometimes fancifully referred to as the Horsethief Route. According to legend, horse thieves would steal horses in Arizona, drive them rim-to-rim using the Tanner and Nankoweap Trails, and sell them in Utah or Colorado (Green & Ohlman, 1995). Then they would reverse the process, stealing in the north and selling in the south. However, not everyone agrees that this activity occurred (Steck, 2002). While we did not see any evidence of horses or thieves in this area, we were excited to see fresh bobcat and mountain lion tracks along the soft and dusty beds of the fault.

Having enjoyed sunny skies and moonlit nights, with the exception of our first evening out of Phantom, we arrived at Nankoweap ahead of schedule. We indulged in what one might call a five meal-meal when we arrived at our cache near Nankoweap Creek knowing that we would have to prioritize space in our packs for chocolate and gummy bears. From there, we hiked along Nankoweap Creek down to the river where we climbed back on top of the Redwall in the Little Nankoweap drainage. For the next 50-miles, all we had to do was contour the Redwall until it disappeared into the river.

MARBLE CANYON

The stretch of the Grand Canyon from the confluence of the Little Colorado River to Lees Ferry is called Marble Canyon. John Wesley Powell named Marble Canyon during his 1869 expedition. He wrote, "We have cut through the sandstones and limestones met in the upper part of the canyon, and through one great bed of marble a thousand feet in thickness" (Brian). The great bed of marble wasn’t marble. It was the Redwall limestone which the Colorado River polishes when it is exposed at river level, making it look like marble. Traveling downstream through Marble Canyon on a boat, like John Wesley Powell did, you witness the emergence and accumulation of each of the colorful Paleozoic layers. Hiking upstream we had the opposite experience.

Traversing the top of the Redwall limestone through Marble Canyon for days, we felt a sense of wilderness that we had not experienced anywhere else during our hike. That was the sense of vertical isolation. While the Sanup Plateau below Kelly Point is miles away from the Colorado River and paved roads on a horizontal axis, walking the Redwall in Marble Canyon you are vertically isolated below the rim and above the river. Although close in proximity, roads and the river lie inaccessible and out of reach due to the sheer walls above and below the Redwall.

When considering the history of Marble Canyon, it was this sheerness of the Redwall limestone that led to surveys for a dam that would have backed up water to Lees Ferry. The Bureau of Reclamation proposed a dam in Marble Canyon as recently as the late 1960’s (Brian). Enormous drill holes as well as telephone wires and infrastructure for a tramway that ran from the rim down to the top of the Redwall are slowly decaying remnants of a project that fortunately never came to fruition.

Arriving at the river near to river-mile 24, it seemed unfathomable that the Redwall was completely gone, having contended with this carnivorous limestone ever since our very first scramble out of Pearce Canyon onto the Sanup Plateau.

Next to disappear were the iron red layers of the Supai group. Although foot-miles walked in Marble Canyon are more closely correlated to river-miles, the hiking is nerve-wracking and tedious at times. The panoramic views of river, along with it’s soothing soundscape, helped to calm the nerves as we did our best bighorn sheep impersonations. Traversing crumbling ledges with a 500 foot drop-off over our shoulders, we knew that one slight skid or stumble and we would likely suffer a fatal fall. After the Supai group is completely submerged, we more or less got to hike at the river level. While no longer having those drop-offs looming over our right shoulder, we were faced with relentless scrambling amidst enormous boulders.

We spent our last night in the canyon at Soap Creek beach. From there the burgers and sweet potato fries at Cliff Dwellers Lodge near the head of the Soap Creek drainage seemed so close and yet so far away. The stretch from Soap Creek to Lees Ferry would be our final long-cut. A long-cut to the best burgers and sweet potato fries on the Arizona Strip. With only 12 river-miles left to cover, we knew that we would have to keep our game faces on. Having walked somewhere in the ballpark of 600-miles at that point, there was one thing that we knew we could never do and that was to underestimate the Grand Canyon. There are no gimmes in the Grand and this stretch would prove to be our grand finale.

The terrain between Soap Creek and Lees Ferry is challenging. Between Navajo Bridge and Cathedral Wash is a 40 foot face climb and exposed ledge traverse above the river that has caused numerous hikers to do an about-face and return to Lees Ferry with their tail between their legs. Some hikers have opted instead to walk along the rim and drop into the canyon near Seven-Mile Draw. But that climb and traverse weren’t the only hurdles. Our grand finale also included bushwacking through tamarisk, scrambling over more giant boulders, crawling across sandy ledges, and wading as water released from the Glen Canyon Dam was quickly submerging the ledges on which we were walking.

LEES FERRY

Arriving at Paria Beach in the late afternoon we were on top of the Kaibab Limestone for the first time since we’d left the South Rim in December. Setting our packs down on the boat ramp at Lees Ferry our hike was over. Even then my eyes kept looking upstream as they had reflexively done for the past 47 days. Looking up canyon and then down canyon, I couldn’t help but think of Robert Benson Eschka and his epic trek. As he hiked upstream towards Moab, he camped down at Salt Water Wash where he made the following entry in his journal:

Although this would be the last night in the Grand Canyon, I did not feel depressed in any way nor did I look forward to any change. By now my mind was trained not to see the park boundary as a termination of the “Grand Canyon.” The physical appearance will change slightly from here on but otherwise I considered myself as being in the middle of one great canyon, still far away from any boundary. So, tonight was just another camp amidst the glamour and beauty of canyon country.

It was hard to believe that we had accomplished our BHAG - the stars had aligned, we had more than a little bit of luck, and the wind for the most part had been at our back. And yet, standing there, I knew that the essence of the BHAG wasn’t in having arrived at the park boundary. Rather, it was all of the terrifying Redwall routes, frigid mornings, and frozen gummy bears. The essence was not in having done it, but in the doing. It was in the time we got to spend below the rim. Author and explorer, Craig Childs explains:

There are many ways to see this landscape, viewing it from a map or plane, seeing it in the art of a pot, reading about it in a book, hearing or telling a story of it, and each has its own truth. But to be here, to witness its ceaseless metamorphosis, entire landforms and artifacts seeming to be arranged, is inescapable.

At 78 years old, George Steck went for his last hike below the rim. His destination was Indian Garden. Savoring the six hours it took to hike 4.5 miles down the Bright Angel Trail, a friend walking with him asked what he’d learned in all of his years of hiking in the Grand Canyon. Last but not least, Steck said with a smile, "All’s well that ends" (Thybony, 2013).

Matt and I crossed our fingers that the car we had parked at Lees Ferry two months earlier would start. When it did, we drove off into the sunset in search of burgers and sweet potato fries.

A resource list is available upon request by contacting Elyssa Shalla.

Images copyright Matt Jenkins, unless otherwise noted.