Ìsland A week in the land of ice and fire

1. 66 Degrees north

It is human nature to seek order and limits. We've applied this thinking to our own world, regardless of the contempt that nature seems to show towards our desire for clear borders. And so we tend to be disappointed when we realize that those imaginary lines we've drawn don't show a clear change in environment at the border. One of these edges is the one we've assigned to the Arctic Circle, currently at about 66 degrees north of the equator the southernmost line at which you get at least one 24 hour day and one 24 hour night. Yet, for a place of such significance, most of the time the world looks the same in either direction from it. Nevertheless every now and then, nature will cooperate and will present an appropriately majestic view north of that line, giving the impression that it is indeed a different world, a world of savage beauty that will extract a steep price from anyone that dares try to trespass in search of untouched wilderness. Such was the view that extended in front of me, the sun moving backwards through the sky and rising on the north, as my flight crossed that imaginary line.

At the other end of the flight, Reykjavík awaited. At just 120,000 inhabitants, it's tiny for a capital city, and with its location of 64 degrees north, the northernmost one too. Being such a small town with not many tall buildings to be found, the cityscape is dominated by the imposing pillars of Hallgrímskirkja, the largest church in the country. Designed to look like the basalt columns found all through the volcanic areas, it pays adequate homage to its Viking heritage, especially when seen in profile against the all-to-frequent tumultuous clouds that come with the storms. It's peculiar to note that the street leading right up to it happened to be decorated with the colors of the gay pride festival that had just recently happened.

The cityscape is dominated by the imposing pillars of Hallgrímskirkja

For all its remoteness and difference of culture, for someone coming from the Pacific Northwest, there was a reassuring sense of familiarity in the air: the rainy weather that doesn't seem to bother people who will walk outside without umbrellas, comfortable in the knowledge that a little rain never killed anyone; the fashion sense straight out of an adventure clothing catalog, everything made of quick drying fabrics and wools that will keep you warm even when wet; the coffee of course, which is not surprising given that Iceland is amongst the top coffee consumers per capita in the world; and the love for the outdoors. All those things will be instantly recognizable to anyone from Seattle, who would, like Icelanders, also know that living in a place with bad weather, is no excuse for bad food. Though I'll admit, I could live the rest of my life without Hákarl (rotten shark)...

But there is one thing that would instantly strike as extremely odd to someone visiting from the Emerald City, the trees, or rather the lack thereof. With a growing season so short that it's measured in days rather than months, there are almost no trees to be found in the island, with most of them rarely having the chance to grow beyond the size of mere shrubs; A reminder -or perhaps a warning- that, in these lands, even the hardiest of life forms, struggle to survive.

2. Into the wild

As Reykjavík faded into the horizon on my rearview mirror, the land around me became just a sparse panorama of grasslands and farms, the famous Icelandic horses being the most common animal that I would encounter around the roads. Further away from the city the vast emptiness of the land became apparent. The pavement stayed with me for a while, but soon enough even that ended as I moved closer to the highlands, the vast uninhabitable expanse of ash and rock that dominates the central area of Iceland. Before reaching that gauntlet, there were still two stops where civilized comforts could be found, two of this country's most famous sights, first off, Geysir, the original, the one that all other geysers are named after.

Geysir, the original, the one that all other geysers are named after.

Long before I saw the steam rising from the ground, the smell of sulfur wafted over the hills announcing that I just have abandoned the domains of the sun; I now walked on a place where the crust that keeps us separated from the molten rock deep below, has become porous and thin, and the ancient heat in the heart of our planet seeps up and invades the water table; Life-sustaining heat here comes from the ground, not the star in our skies. Rumblings underneath my feet joined in with the columns of steam as water interacted with magma in the tunnels below, boiling and roiling until enough energy accumulated and had to escape with only one exit available to it, up... Boiling water gets thrown upwards of 40 feet at a time; the tangible proof of the pulse of the planet explodes before you every couple of minutes, droplets turning into steam when the pressure is released and condensing back into water a few seconds later in the cold Icelandic air, to fall back into the pool where it will collect and heat up until the next time the steam builds enough pressure to escape its confinement.

Water boiling and roiling until it heaves up to release all that energy

At Geysir I could preview what laid ahead, the rugged terrain, the alien landscapes. Yet there was still the comfort of a hotel and a fine restaurant next to the geothermal area. The next stop wouldn’t be as comfortable; the last bastion of civilization before the land gives in to the untamed wild, the golden falls, or Gullfoss for the locals. A 32 m waterfall where the roaring Hvítá River seems to be swallowed whole by the ground as it plunges into a crevice hidden from view by the soft rolling hills that surround the area. It's only when one goes down the wooden staircase that the full magnitude of the spectacle is revealed.

After walking through the mists of the Gullfoss, I came back up the staircase to stare into the horizon. I could see the fields of green recede into the rocky, craggy domains of the ancient mountains and glaciers of the highlands, and, to my right, a warning to beware the road I was about to travel; the twisted metal of a wreckage. Probably left by someone that didn't pay enough attention to the unpaved road and found out just what price the land might exact for your distraction.

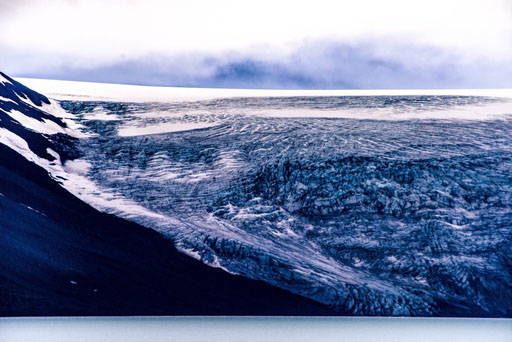

The change of scenery was surprisingly quick, in much less than a mile, the green pastures gave way to endless rock and dust, broken only by the occasional oasis of green by the side of a small stream of glacial melt. Life here is close to impossible; water filters so quickly through the porous rock and volcanic ash that there's no moisture to be found for vegetation, and the air that comes down from over the glaciers is cold and dry, this is not a place where you want to be stuck. But, as inhospitable as it is, it receives plenty of visitors looking to experience the alien landscapes and rugged beauty of the lava fields, the mountain ranges, and most of all, the jöklar, the mighty Icelandic glaciers.

Endless rock and dust, broken only by the occasional oasis of green

Langjökull, the second largest of these glaciers, is also the source of Hvítárvatn, a large glacial lake that outflows south until it eventually reaches the golden falls, but way before it reaches that popular tourist destination. Its waters feed a small oasis in the middle of the harsh terrain of the highlands; a handful of old hunting lodges dot the edge of the water; a nice place to stop and take in the scenery, maybe even spend a night or two. Then again, they were not for me on this particular trip; my destination laid much further north, at Hveravellir, a small campground built next to a geothermal area where a lot of the long distance trekkers and bikers stop for a couple of days to rest and re-supply. By the time I arrived, nightfall had already fallen and a storm was rolling in. For the people sleeping in tents, this was going to be a restless night.

In few other places in the world, does it become so obvious why our ancestors would come up with all sorts of legends and stories to explain the natural world. In Iceland though, the landscapes are so alien and so unlike anything you've likely seen before, that your mind begins to race in wonder and imagine all sorts of mystical sources for the oddities before your eyes; the slow steam rising all around you in the morning twilight, the bubbling pools of sulfurous water that sometimes pop up right beside the trail as you walk on it. It's easy for the basic outlines of a legend to sketch themselves in the back of one’s mind if one stays here long enough. Nevertheless, Hveravellir has already a legend of its own, and one based much more in facts than whatever your mind could concoct in the midst of the wonderful surroundings; there is a stone hut in this oasis, dated to back in the 18th century. Its origins aren't certain, but the local legend talks about an outlaw, Fjalla-Eyvindur, who, like most outlaws in Iceland at the time, was exiled to the highlands, which would usually mean a death sentence, but as luck would have it, he found this geothermal area.; here, the extra warmth and water that spring forth from the ground, allow grass to grow, which gave him a perfect place on which to graze sheep which he, not surprisingly, stole from the nearest towns, an act made easier by the fact that most sheep farming in the island is done in a fully free range fashion. Something that became annoyingly obvious as I got closer to the end of the highlands where I ran into plenty of sheep blocking the narrow dirt road. On the plus side, it's a sign that one has reached civilization once again; I now approached Akureyri, Iceland’s second largest city

Landscapes so alien and so unlike anything you've seen before

3. The northern town

Slightly north of 66 degrees of latitude, life goes by at a slow pace. Nowhere else is this more obvious than here, on the northern side of the country, where the small town of Akureyri lies, tucked in at the end of a narrow bay that provides a perfect natural harbor for a fishing town to spring up. The people here walk around enjoying the fairly temperate weather for a place that practically sits on top of the Arctic Circle; the hilly terrain affording them beautiful views of the bay and providing room for some of the very few trees that you'll see in Iceland. On top of it all, the twin towers of Akureyrarkirkja, stand guard over the peace and quiet of a town that needs only 5 police officers in active duty at any given time.

The twin towers of Akureyrarkirkja, stand guard over the peace and quiet of the town

Less than 18,000 people call this town "home", and the whole city still feels very much like a tiny fishing outpost, with traditional looking buildings adorning its main street and a tiny public marina providing shelter for a couple of sailing boats right next to the town's cultural center where a statue of a fishing boy stands forever guarding the pier and the children that constantly play on it. As I left this place, the road rose sharply as it rode the skirt of the mountains on the other side of the bay, providing a last glimpse of the full town, its docks dwarfed by a cruise ship making a stop in one of the few shelters on the northern sea. From here I would now travel east, following the ring road all the way around the rest of the island until it takes me back to Reykjavík. But first, I had to meet with the glaciers again, this time at the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon 500km further down the road.

A fishing boy forever guarding the pier and the children that play on it

4. The ring and the ice

Hringvegur, the ring road, 1,332 km of pavement that go all the way around the island, in the process showing a little bit of everything the country has to offer. sometimes, just over a hill you can see an ancient lava field, stone bubbles still frozen in a rolling turmoil of volcanic fury, give way to soft sloping hills of green that just a few kilometers later turn into a barren field of sand and rock where prismatic patches of blue and green show the places where gasses are exchanged from deep below the earth, leaving exposed residue deposits of sulphur and calcium. Many streams cut through the land here providing welcome resting spots with cool fresh water and beautiful waterfalls so numerous that it's hard to remember them individually. Many of them even have hiking trails where one could spend weeks and still not see half of all the vistas that abound just around the highway. And there's also the fjords, with mighty storms constantly stirring up the waters off the coast, the dangerous looking clouds providing a perfectly cinematic background to the steep cliffs where the waves break into the coastline, forever eroding the land that the volcanoes keep creating.

Mighty storms, constantly stirring up the waters off the coast

South, south across the black desert, through the fjords and the breaking waves of the ravaged coast, as the sun sets on the north I finally got to look on down from the bridge into the still waters of the Jökulsárlón In the tenuous light of the arctic midnight, with glimmers of light reflected on the clouds from the shining ice caps up at the north pole, the icebergs float calmly in a silence broken every now and then by the distant rumble of the calving glacier and the loud cracks of the thermal stresses on the ice, shattering the ghostly giants as they travel ever closer to the ocean where many of them will end up on the black shores of the ashen beaches of Ísland.

The stormy weather picked up during the night which, with the remoteness of this area and its closeness to the glaciers, made this one the coldest night I've had the whole trip. The payoff the next morning was worth it though. The heavy winds had cleared up the sky and I finally got to see some blue skies. Although they seemed pale in comparison to the deep blue of the icebergs floating out to sea. As I hiked further out, away from the road, I found a few camps dotting the sides of the young lake. A lake so young it has only existed for about 60 years. There are still plenty of people alive in the country that remember a time where this gem of a place did not exist, until the warming earth caused the glacier to retreat inland, leaving behind the beautiful corpse of the river of ice. The crevices and cracks that cover the glacier are easily visible here, and I wish I had more time to walk out all the way to the wall of ice that beckons just beyond the next hill, but my time in Iceland had come to an end. I had a plane ticket out of the country and needed to drive the last 200km back to Reykjavík before the day ends. The plane hadn’t even made it halfway through its trip, before I had to break out pen and paper to start planning my next visit to Iceland.

The beautiful corpse of the river of ice