We(Sort of). Are. Clemson. erin smith

When students come to college, they’re usually excited to meet people like themselves, friends to laugh with, to take classes with; they’re looking for their niche.

This is made all the more difficult for minority students on an undiverse campus, such as Clemson University. African-American minority students experience biases against them in education and curriculums, despite the recent pushes for inclusiveness; new curriculums need to be developed and teachers need to understand how to educate all students rather than catering to only the majority, especially at a university such as Clemson.

The new expectation is that individuals become aware of everyone’s different viewpoints, respect them, and learn and grow from them. The same should be done in the classroom setting, specifically the classrooms at Clemson. Clemson’s curriculums, and those who teach them, need to be more aware of the needs of their students, all of their students.

It is safe to say that Clemson is primarily a white university, diversity is not one of the school’s strengths right now; it has even been stated that Clemson, “...has the smallest share of African-American students of any public four-year S.C. college,” (Shain, 1). Not to mention issues like the refusal to change the name of Tillman Hall and racist actions like the “Cripmas” fraternity party (Shain, 1). Regardless of what side of these controversies people choose to be on, it is easy to see why a black student at Clemson would feel unheard, and even oppressed.

These feelings translates into Clemson’s classrooms as well. Not only can the lack of diversity make minority students feel unwelcome, but also breeds more ignorance about minority issues. As mentioned previously, “Cripmas” was an incident in which a fraternity hosted party encouraged students to dress like gang members (Shain, 1). After the “Cripmas” incident, President Clements met with fraternity representatives and African-American students.

A.D. Carson, founder of diversity campaign See The Stripes, attended the meeting and said,

“It felt intimidating,”

(Shain, 1), as there were a small number of African-American students as opposed to the fraternity representatives.

This was only one meeting, but imagine walking into a similar situation in every classroom you walked into. You too would feel out of place, unwelcome, maybe even tempted to leave.

An analysis of minority dropout in higher education, comparing the United States with Norway, found that minorities have a higher risk of dropping out of higher education, as compared to majority students in both countries(Reisel and Brekke, 705).

The analysis also found the dropping out appeared to be based on socioeconomic background in the United States (Reisel and Brekke, 705). However, minority students are socioeconomically at a disadvantage in Norway as well, but the minority students did not have a higher dropout rate, as compared to the majority students in Norway (Reisel and Brekke, 705-706). The minority students were still at risk of dropout, yet their dropout rates were not higher than majority student dropout rates (Reisel and Brekke, 705-706). While the reasonings for this difference between the United States and Norway are complicated, one has to wonder if the structure of the United States education system is at fault. While it has been proven that those at risk from dropout often come from low socioeconomic background, it is necessary to look more closely at why minority students would drop out.

While the dropout rate for black students compared to white students is significantly lower for the United States as whole, this is not true of every university.

As of 2005, the graduation rate at Harvard University for black students is 95 percent and eleven other top universities graduation rates for black students are above 85 percent (JBHE, 89).

It is clear that these students are entirely capable of completing their education at universities with high standards. One factor contributing to this, is the efforts these schools make to ensure all students feel welcome. Many of these universities, “ have set in place orientation and retention programs to help black students adapt to the culture of predominantly white campuses,” (JBHE, 90). While there are other contributing factors, this information shows how feeling welcomed by the university had a positive impact on the graduation rates of these black students. Low socioeconomic standing is a large factor leading to a student dropping out, yet minority students also face feeling unwelcome and being constantly aware of their minority status, if the university they attend does not strive to change this.

Is Clemson’s curriculum inclusive enough for minority students?

Are minority students able to relate to teachings on a personal level?

These are difficult questions to answer.

Unfortunately, Clemson’s faculty also suffers from a diversity problem, less than four percent of the full-time staff are African-American, and so far, nothing is being done to change this (Shain, 1). Not only are minority students coming into classrooms where they could be the only minority student, but they are likely being taught by mostly white professors. Many may think, while this is unfortunate, they are still learning and it does not matter who teaches them. However, positive and strong student-teacher relationships have been found to make teaching strategies more effective (Marzano, 1). If a teacher is not a minority, or has not been taught how to be inclusive, it would be rather difficult for them to connect to minority students and therefore more difficult to effectively teach them. A stronger effort needs to be made to diversify Clemson as a whole. With a more diverse staff, more of Clemson’s students will be able to connect to their teacher and to what they are teaching.

This also brings up the point of curriculum, and whether it is properly shaped for all students. Clemson has a dark past, the land the school sits on once held a plantation and had slaves. Rhondda Thomas, an African-American literature professor, noticed that the tours of Fort Hill did not mention slaves (Shain, 1).

People think that hiding Clemson’s shameful past is less harmful, when in fact it is from history that humanity learns its biggest mistakes and strives to avoid them in the future.

It is as A.D. Carson said in his video starting See The Stripes, “And if that is an uncomfortable truth for the institution, so be it. These are the stripes we bear, so see them. Slavery, sharecropping and convict labor paved the streets and sidewalks of this ‘high seminary of learning’...” (“See The Stripes”, 1).

Students cannot truly be prepared for the world if they are only taught to see the good; it is the duty of their education to show them the truth.

Clemson has made some efforts to listen to their students. Rhondda Thomas’ research into the convict laborers who constructed the original campus led to a series discussing race on campus, and Fort Hill has added an exhibit about the slaves who lived there (Shain, 1). The Diversity Office regularly holds events educating students about different cultures. The Gantt Multicultural Center was opened in August 2015, the Center advises: the Black Student Union, Council on Diversity Affairs, Gay Straight Alliance, Latinos Unidos, International Student Association, and the National Pan-Hellenic Council (Gouch, 1). Five Clemson students also started the Minority Student Success Initiative in 2011, which puts on events, features programs, and provides other services all dedicated to the success of Clemson’s minority students (“Clemson MSSI”, 1). While these are all positive occurrences, had people not brought the public’s attention to these issues, or sought to solve them, it is unlikely the administration of Clemson would have felt compelled to implement these actions.

Even though Clemson has made some progress, it is not enough. The curriculums need to be made more inclusive, so that students can relate to what they are being taught. American curriculums are often accused of “master scripting”, when “...classroom practices, pedagogy, and instructional materials... are grounded in Eurocentric and White supremacist ideologies,” (Swartz, 341). Not only could this create misinformation, but also alienates minority students from their learning. It is the duty of the university to be considering what it is teaching its students. If indeed any “master scripting” is occurring, the administration should be taking steps to prevent this. Staff should themselves be taking courses on the importance of inclusive teaching and how to incorporate this into their curriculums. Course wide syllabi should be constructed with care to prevent such biases from occurring. Textbooks should be evaluated to ensure that they are not biased against minorities or have “master scripting”. These ideas would take a large effort, and likely budget, to accomplish, so the key is to gradually implement them. Clemson’s administration may not consider these a high priority, yet steps need to be taken to solve the underlying issues of Clemson’s diversity.

Clemson must stop simply creating band-aid solutions when the public notices wrongdoing, and fix the issues at our core.

Diversity at Clemson is a large issue that we face. Not only in the student population, but also in the faculty, and action needs to be taken. This lack of diversity can easily affect minority students academically, analysis has even found the higher education dropout rate to be higher in minorities. Students that don’t feel welcome on campus and can’t connect to their educators will not only feel unwelcome, but also suffer in their ability to learn. Clemson has made efforts to be more diverse and inclusive, but only after incidents occurred showing the public just how necessary diversity and inclusion are to Clemson.

The curriculums themselves also need to be scrutinized, is the entire truth of Clemson being taught, and are any racial biases occurring? It is important that students learn all of the truth, to prevent the mistakes of the past from occurring again. Some of the ways to go about this are to educate Clemson’s staff, and to inspect the syllabi and textbooks for any “master scripting”, unintended or otherwise. People simply need to be aware of the diversity issues here on Clemson, and proactively change Clemson to be more inclusive for all students.

If We Are Clemson, we need to mean it.

Works Cited

Blahedo. Fort Hill. Digital image. File:Fort Hill.jpg. Wikipedia, 15 June 2006. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

"Clemson University Minority Student Success Initiative." Clemson University Minority Student Success Initiative. Clemson University, 2011. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

Gouch, John. "Gantt Multicultural Center Opens in Clemson University Union." The Newsstand. Clemson University, 18 Aug. 2015. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

Kalsi, Dal. Graffiti on Tillman Hall. Digital image. Clemson University Police Investigating Graffiti on Tillman Hall. WBRC Fox 6 News, 7 Jan. 2016. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Marzano, Robert J. "Relating to Students: It's What You Do That Counts." Educational Leadership. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Mar. 2011. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

OzelotStudios. Norge- Flag of Norway. Digital image. OzelotStudios. DeviantArt, 13 June 2012. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Reisel, Liza, and Idunn Brekke. "Minority Dropout in Higher Education: A Comparison of the United States and Norway Using Competing Risk Event History Analysis." European Sociological Review 26.6 (2010): 691-712. JStor. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

"See the Stripes." See the Stripes. See The Stripes, 2016. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

Shain, Andrew. "'Pepper in the Salt Shaker' - Clemson Hears Calls for More Diversity ( Video and Photos)." The State. The State, 31 Jan. 2015. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

Simien, Jessica. Clemson Fraternity Cripmas Party. Digital image. Fraternity Suspended For Gang-Themed ‘Cripmas’ Party. Jessica Simien & Simien Media Group, LLC, 9 Dec. 2014. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Swartz, Ellen. "Emancipatory Narratives: Rewriting the Master Script in the School Curriculum." The Journal of Negro Education 61.3 (1992): 341-55.JStor. Web. 21 Mar. 2016.

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. "Black Student College Graduation Rates Remain Low, But Modest Progress Begins to Show." The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (2005): 88-96. UVAToday. University of Virginia, 2006. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

Think0. United States USA Flag. Digital image. Think0. DeviantArt, 19 Aug. 2011. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

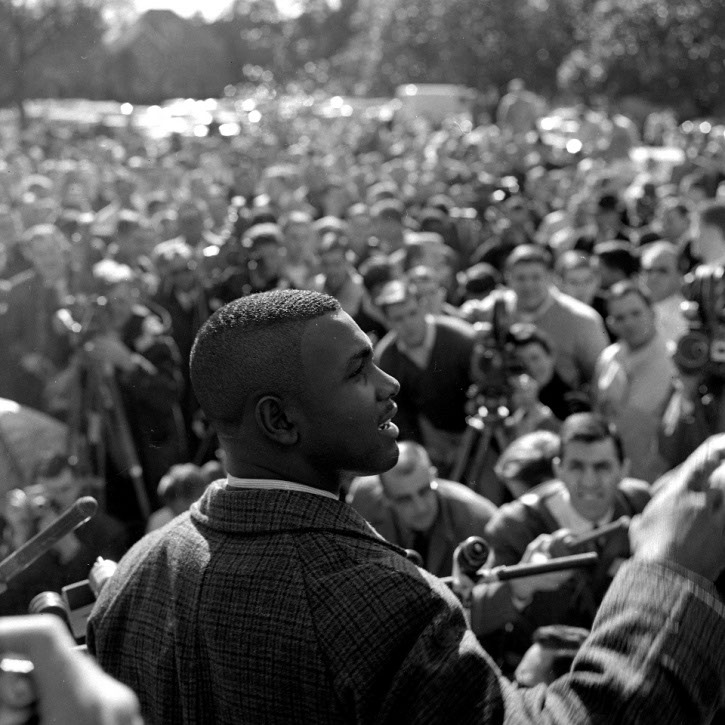

Williams, Cecil. Gantt and Reporters upon His Entrance to Clemson Jan, 28, 1963. 1963. Clemson. Newsstand. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.