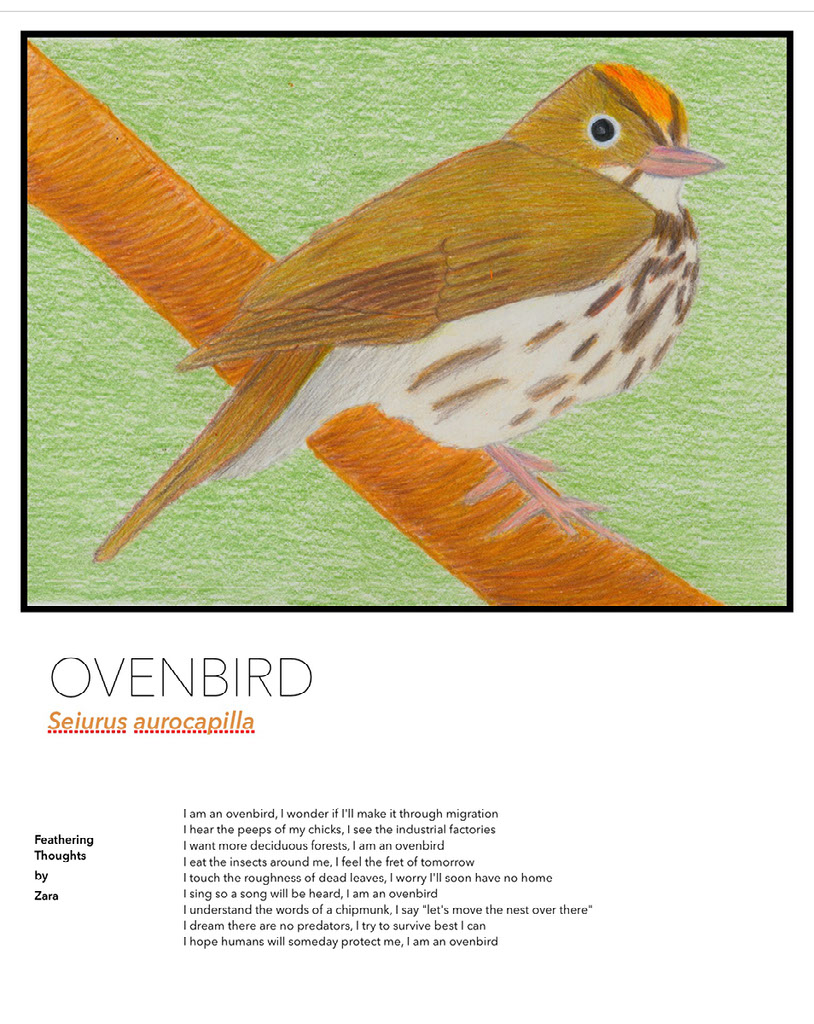

Ovenbird Seiurus aurocapIlla

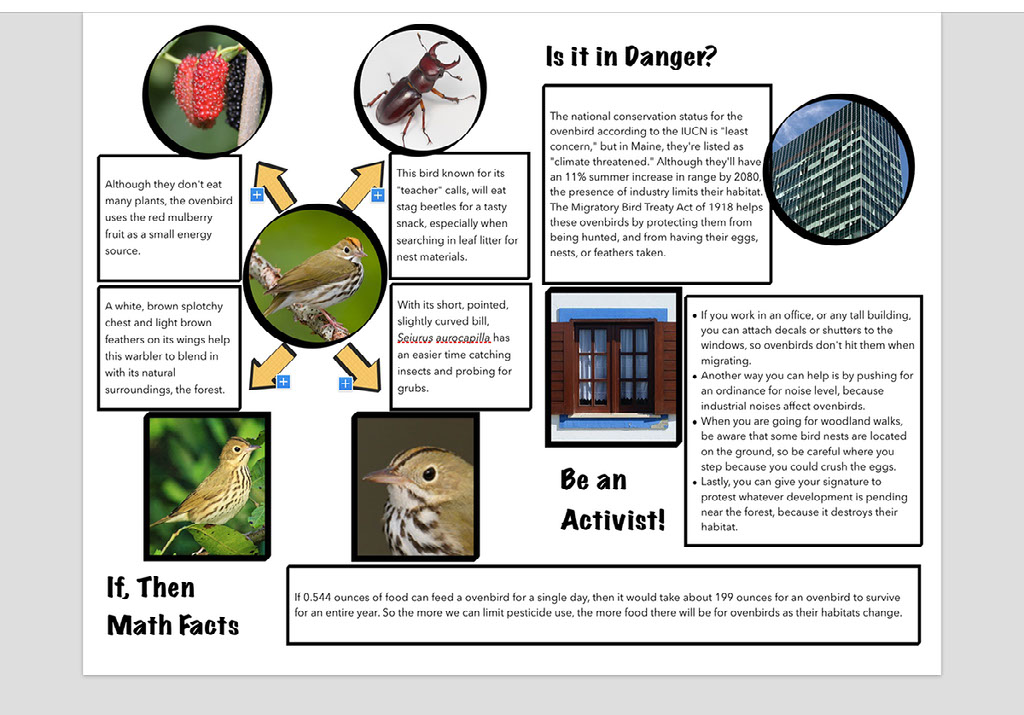

Ovenbirds are thrush-like warblers, with the appearance of a thrush, and in the family of warblers. Their call sounds as if they are saying "teacher." This bird is an omnivore and a secondary consumer, so it can be predator or prey. The ovenbird's appearance helps a lot with camouflage. Since it has a brown splotched white stomach, it is able to blend in with the sky and tree branches when seen from below. Also, since this warbler has a brownish green back and wings, it blends into the trees and leaf litter when seen from above. The bill has a purple/brown top, and a light pink/brown bottom, it is wide at the base and pointed at the tip, it is slightly curved, used for catching insects. The legs are a very light brown/pink, and are very short, without feathers until they meet the body, used for walking and foraging. The feet are light pink/brown/red feet, with clear/pink claws, and has 3 toes forward and 1 toe back, used for perching and catching insects. The male ovenbird has two dark brown stripes down its head with a bright orange stripe in between, it has a white ring around its black eyes, and a light brown wing and head, its stomach is white with dark brown splotchy spots, and the white continues all the way up to the beak. The female ovenbird looks the same as the male, but the orange stripe that the male has is a light orange/brown on the female. The differences between the two genders is called diversity, just like between other ovenbird individuals. Although the ovenbird doesn't have mutualism with any organism, or any known commensalism with any species, it does have symbiosis. The ovenbird has symbiosis with the Veery, because they are two of few birds that nest on the ground. Also, they both can eavesdrop on chipmunks conversing with each other, so they know where to keep their nests from. The ovenbird does not have much mimicry for survival, but has been spotted mimicking the red-eyed vireo song. It has also been seen mimicking the songs of the robin, purple finch, and the white-eyed vireo. In the year 2015, the highest count of the ovenbird's population was 33,865 ovenbirds in the month of May.

Ovenbirds and usually between 4.3-5.5 inches long. Ovenbird's eggs have about the same shape of a chicken egg, only smaller, and are white with little brown dots all over them, location of dots may vary. 3-6 eggs will most likely be laid, and they will hatch in 11-14 days. Ovenbirds migrate to South America, the Caribbean, Mexico, and to the southeastern United States. They migrate in the Spring, and and Fall. When eggs have been laid, only the female sits on the egg to help it incubate, but when it has hatched, both parents help to feed the chick. The egg is about 2.1cm long, and about 1.5cm wide. Also, when a predator comes near the nest, the female continues to protect the egg until the last possible moment, then they pretend to be injured to lead the predator away. Ovenbirds live for at least 7 years.

The Ecosystem

The ovenbird's ecosystem is the mature stage of the deciduous forest (a climax community), this is also the 4th stage of ecological succession. Ovenbirds don't live in pioneer communities because they prefer the protection of leaved trees, and dead leaf litter. These abiotic (nonliving) factors cannot be found in coniferous forests. Deciduous trees have leaves, unlike coniferous trees with needles and cones, hence their name. Deciduous trees are crucial to an ovenbird's lifestyle because they need the leaves to make their nests on the ground. Deciduous forests can also be called limiting factors, because this habitat is inhabited with lots of insects, making it easier for ovenbirds to survive. Other necessities for their nest can be twigs, bark, grass, and even animal hair can come in handy.

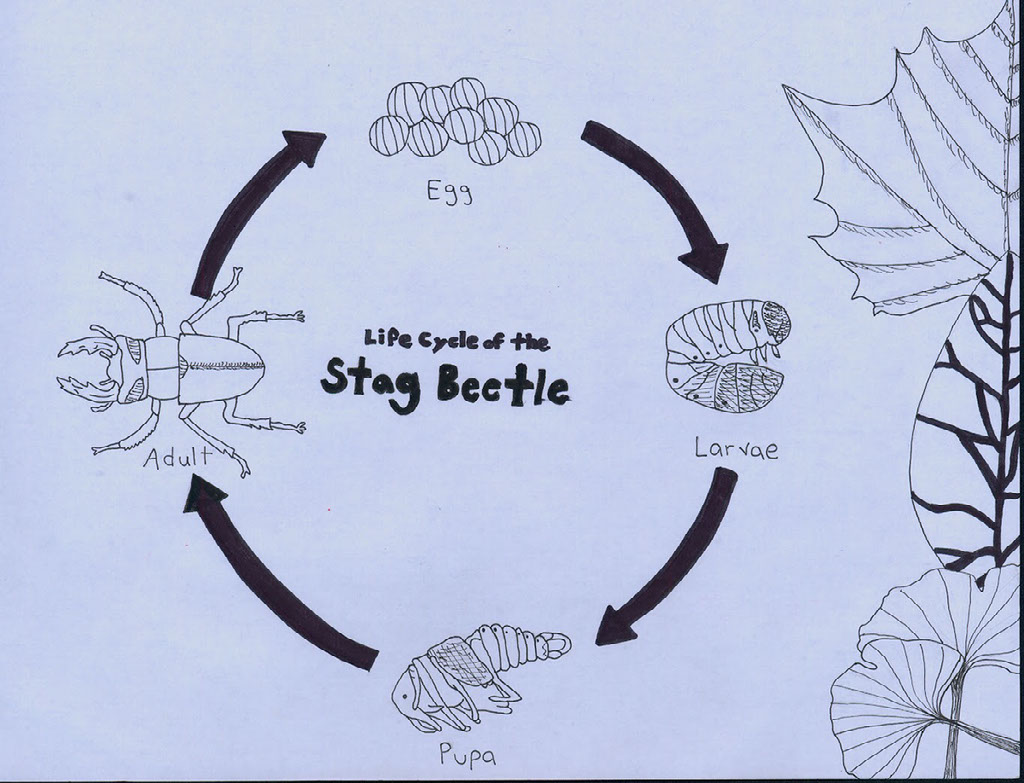

Another requirement to an ovenbird's lifestyle is lots of insects. An ovenbird's diet mainly consists of forest bugs, any they can find. Among the many it consumes is the stag beetle. Stag beetles have a life cycle of egg, larvae, pupa, and adult. They can live almost anywhere, from hot to cold, and dry to damp. Their diet includes leaves, wood, seeds, and fruit. Stag beetles are herbivores, biotic (living) factors, and are primary consumers.

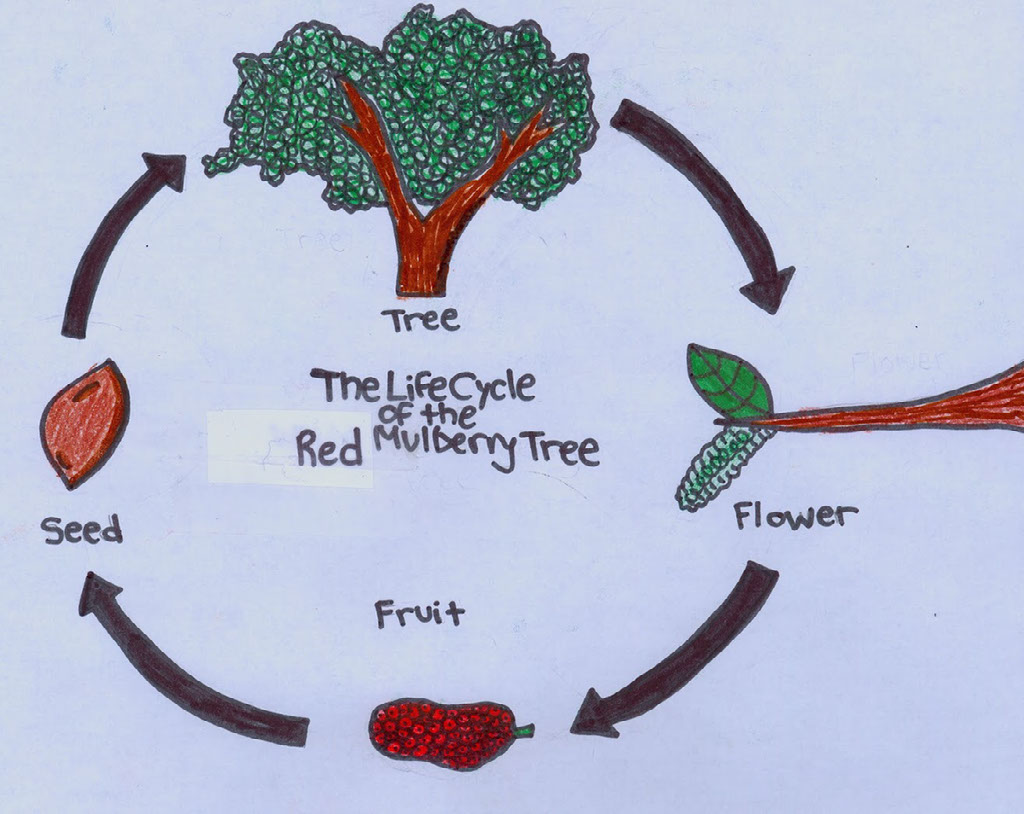

Despite the ovenbird's mainly insect diet, some may munch on a red mulberry or two, from time to time. Red mulberries are the only species of mulberries that are native to North America. The red mulberry tree's life cycle is seed, seed with leaves, seedling, small tree, growing tree, and mature tree, but it can be simplified. Red mulberries get their energy from sunlight and water, and can grow on monoecious and dioecious trees. They are primary producers, biotic (living) factors, and use photosynthesis.

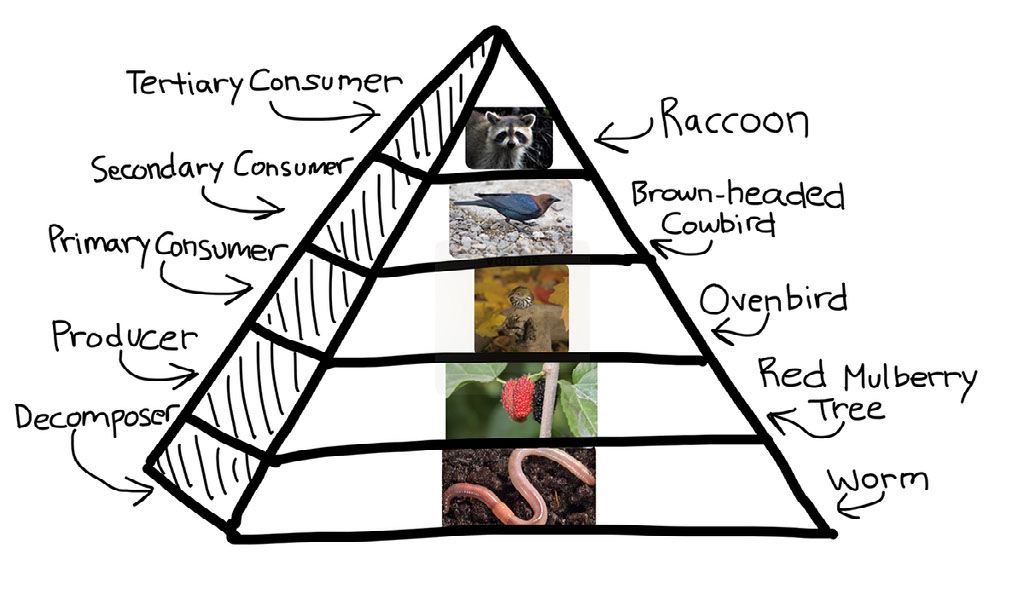

Energy Pyramids

Energy pyramids are a very important part of an ecosystem. They establish who are predators and who are prey. Basically, who eats who. The many levels of an energy pyramid vary according to the ecosystem. In my example, the levels from base to top are decomposer, producer, primary consumer, secondary consumer, and tertiary consumer. Some may call the tertiary consumer the apex predator depending on how big the pyramid is. In the deciduous forest, there are many energy pyramids, such as this one:

Parasitism

Parasitism is also apart of an ecosystem. Parasitism is one species being harmed while another is being benefited. Ovenbirds have parasitism with the brown-headed cowbird. The reason the brown-headed cowbird is a parasite to the ovenbird is because it harms its chicks. Brown-headed cowbirds will lay their eggs in an ovenbirds nest so they do not have to care for them. Unfortunately, the ovenbird does not register that this bird or its egg are invaders, so they will raise the egg as if it is their own. Eventually, the brown-headed cowbird chick will hatch before the ovenbirds, which is a problem. Birds that hatch first have a better chance of survival than the rest of the eggs, so the adult ovenbird will raise the parasite bird believing it has the best chance of survival. Then, the newly hatched brown-headed cowbird will eat the rest of the eggs, and leave the adult ovenbird eggless.

Why They're Endangered

Global Warming and Habitat Loss

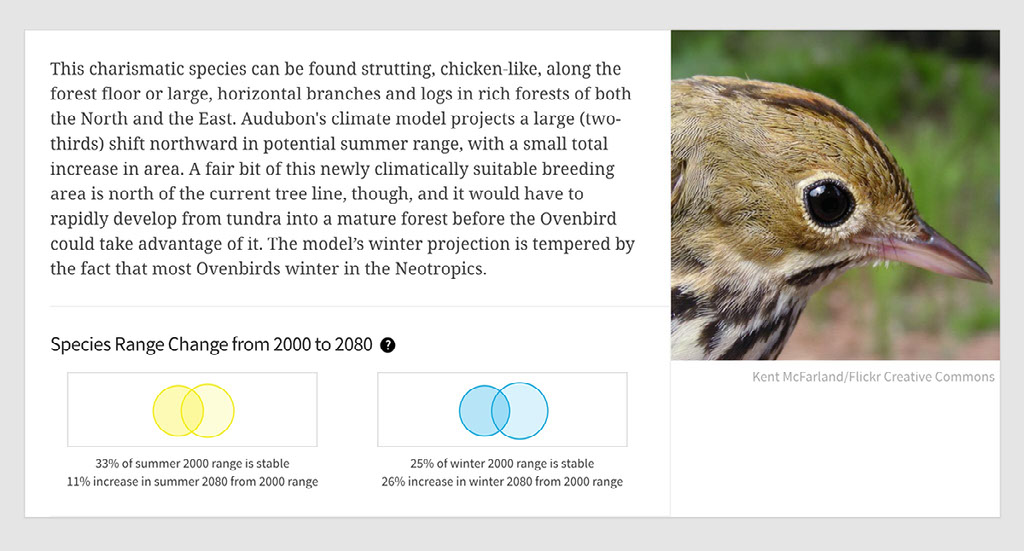

The national conservation status for the ovenbird according to the IUCN is "least concern," but in Maine, they're listed as "climate threatened." Although they'll have an 11% summer increase in range by 2080, the presence of industry limits their habitat. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 help these ovenbirds by protecting them from being hunted, and from having their eggs, nests, or feathers taken. Ovenbirds are threatened because of global warming and climate change are causing them to more north than ever. This is an act of survival, but causing their numbers to decrease frequently. Most ovenbirds live in New England, in the USA, and in southern Canada, but with current climates, ovenbirds are changing their habitat range. This would not usually be a conflict, but the places where ovenbirds are migrating to are covered with mostly industrial factories. These industrial factories are a big problem to the population of ovenbirds because their habitat is unavailable where all of the industry is. Ovenbirds need deciduous forests to make their nests, and for protection, but these woodlands are not located there. Here some photos are ovenbird range, courtesy of the Maine Audubon Society:

As you can see in the two diagrams above, ovenbirds have been changing their range overtime for about 20 years. Soon, ovenbirds will have no presence in the United States of America whatsoever. If we don't make changes, and fast, they will be left to forage for habitat on their own, with little chance of survival.

Windows

Tall buildings with lots of windows are also an issue. When ovenbirds are migrating, they see a building's window and think nothing of it. Then they fly straight into it, and fall the 10 stories or so to the ground. If there isn't something opaque in their way, ovenbirds assume there is nothing there, and this can be a big problem during migration. Millions upon millions of birds die every year just from hitting windows, and these collisions have to stop.

King's Expedition

I am a student at King Middle School (KMS), an expeditionary learning school. Our York 7 expedition was called "It's For The Birds." In this expedition, each student chose a bird from the Maine Audubon Society's threatened list, to study. Since September, we have done many activities and projects to help us learn as much about our birds as we can. Also, The Maine Audubon Society will recieve the final products each student makes about the bird they're studying, and use our work to teach others about the birds. The bird I have been studying is the ovenbird, here are some pieces I have made regarding my studies:

I Am Poem

I am an ovenbird,

I wonder if I'll make it through migration,

I hear the peeps of my chicks,

I see the industrial factories,

I want more deciduous forests,

I am an ovenbird.

I eat the insects around me,

I feel the feet of tomorrow,

I tough the roughness of dead leaves,

I worry I'll soon have no home,

I sing so a song will be heard,

I am an ovenbird.

I understand the words of a chipmunk,

I say "let's move the nest over there",

I dream there are no predators,

I try to survive best I can,

I hope humans will someday protect me,

I am an ovenbird.

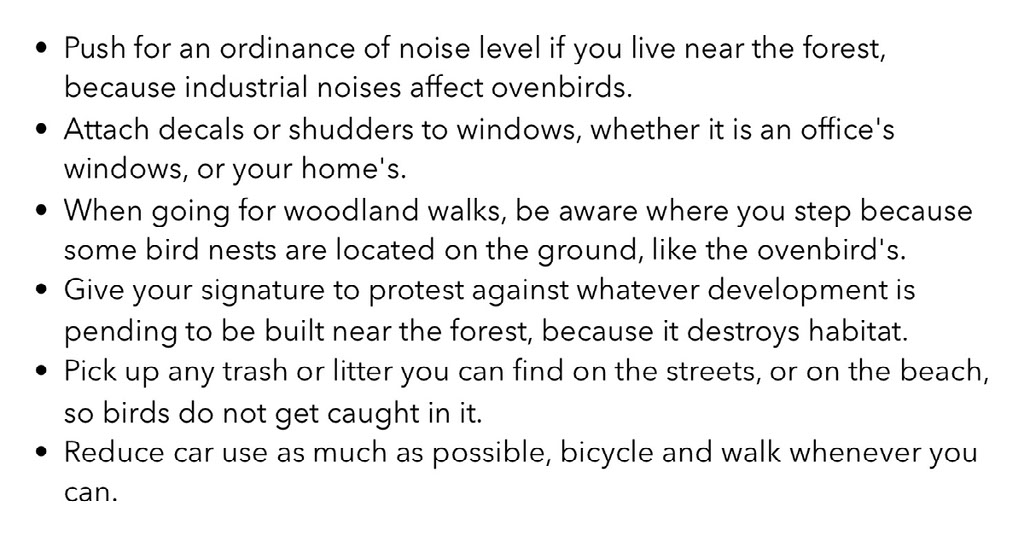

What We Can Do To Help

Stopping global warming fast enough to save all endangered bird species is a hopeless cause, but everyone can do something to help these creatures in need. It could be as simple as picking up a piece of trash you see on the beach, or as incredible as limiting everyday transportation to only riding your bike. Here are some useful ways YOU can help:

By: Zara Boss