Car Design A Tall Tail by Doug Nye

Two hugely significant factors have advanced top-level race car design from virtually a black art into today’s highly sophisticated, cutting-edge – and admittedly often deadly boring (!) – science. One has been the development of onboard data acquisition, measuring and test data. The other has been the developing appreciation of aerodynamic effect – and its harnessing – from the airstream enveloping the car, and engendered by its movement through the vital fluid that we all breath to survive.

The earliest race cars lacked even the most rudimentary devices to ease their progress through the air. Driver and riding mechanic were completely exposed to the airstream, laden as it was in those pioneering days with dust, grit, stones, birds and even the occasional unfortunate beast of burden – or luckless human pedestrian.

‘Windcheating’ bodywork features slowly emerged. An upturned boat shape with sharp pointed prow fared-in mechanicals and crew combined – though development of a transparent airstream-friendly windscreen lagged way behind and crews were still exposed to a battering from the chest up. Fred Marriott’s 1907 Stanley ‘Rocket’ Land Speed Record car epitomized the upturned-boat school of aerodynamic thought – punching the smallest possible hole in the air while easing its flow around, and over, the car-body surface itself.

Concentration upon easy air-penetration, low-drag propagation, ‘slipperyness’ through the air dominated motor racing’s aerodynamic thinking for decades to follow. A few far-sighted and free-thinking pioneers emerged. Swiss engineer/driver Michael May was one, rigging an aerofoil wing on struts above his Porsche 550 and trying it during practice for the 1956 ADAC 1,000Kms at the Nurburgring in Germany. Race officials then told him that he’d had his fun, now stop larkin’ about and take off that stupid thing or we won’t let you start in the race. He took it off, but not before this photograph had recorded the forward-looking device, as available in our Revs Digital Library – here:

May’s grasp of the aerodynamic basics involved still impress – note the vertical end-plates to clean-up and enhance airflow effect over this pioneering Swiss-German wing. If only some of Formula 1’s ‘pioneering’ winged wonders of the 1960s had shown such awareness…

Of course it was boyhood aeromodeller Jim Hall of Midland, Texas, who has taken top honours for his race car aerodynamic advances in the mid-1960s. After producing his first slippery conventional front-engined Chaparrals it was the composit glass-fibre chassised rear-engined design that Jim regarded as his first ‘proper’ Chaparral-Chevrolet. In original form it featured an exceptional high nose, with a curving under-nose panel merging back into an inverted-aerofoil side elevation. Its purpose was to generate lift but downwards, drawing the car down to the road surface beneath. Unfortunately while the bald theory of inverted lift would have worked at altitude, as in an aroplane in free air, it failed within 4-6 inches of the track surface due to ground-effect cushioning. In contrast the nose’s upswept underside generated massive vertical lift and when tested at Hall’s Rattlesnake Raceway team member Frank Lance recalled how “Jim said that the front wheels came off the ground on the straightaway”. A snowplough chin spoiler was then developed as an “under-nose draught excluder”, seen here:

For Sebring 1963, Hall’s partner Hap Sharp wanted the front-engined works Chaparrals to run similar bodywork to that being developed for the new rear-engined car. The curious-looking result became even more curious when the team’s 1963 Sebring 12-Hour entries were protested, apparently by Ferrari’s Luigi Chinetti, and tall fins and shields had to be added overnight to comply with latest FIA regulation screen and door height. Again, trawl through the Revs Digital Library to study the beauteous result:

From chin dams and whisker spoilers to tail dams and flippers, Hall and Sharp and GM R&D’s best brains sometimes tentatively, sometimes boldly, explored aerodynamic effect in search of assisted roadholding, grip and traction and quicker times around a road-circuit lap.

For the 1966 CanAm Championship Chaparral delivered two 2E cars with tall strutted rear wings for Jim and Phil Hill to drive. These ground-breaking new devices were true jaw-droppers for all their rivals. Just study the Chaparral-Chevrolet 2E’s unworldly pioneering form here:

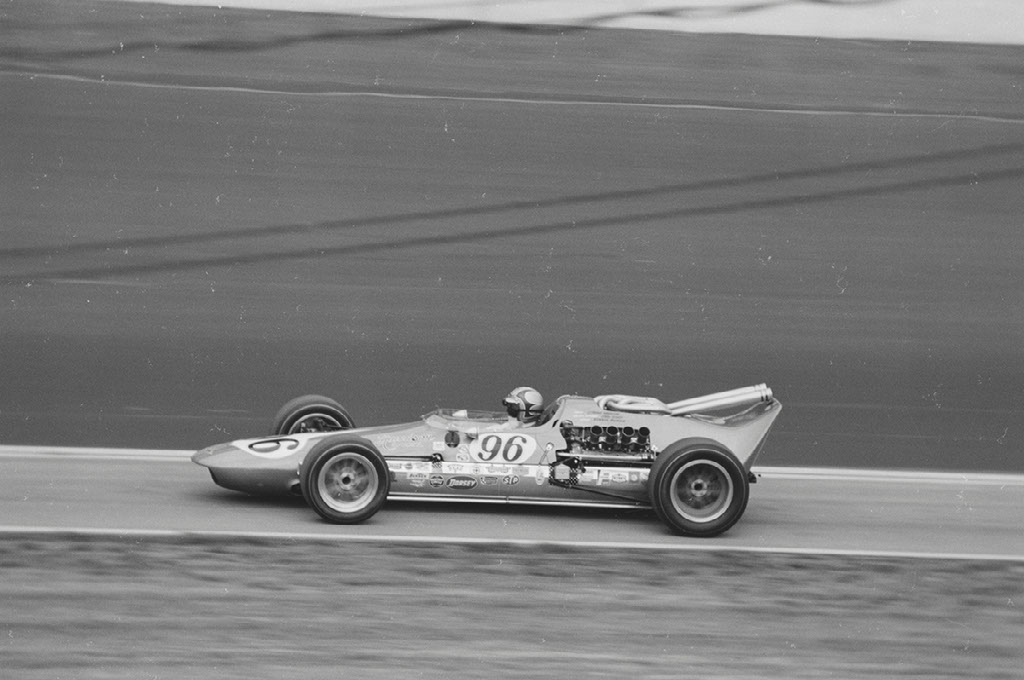

But as the serious student trawls through our Library just consider the dates of such innovation. That Bridgehampton CanAm round – and the high-winged Chaparral 2Es’ public debut in anger - took place on September 18, 1966. Working laterally, let’s take a look at a different racing discipline – USAC Indy cars. Consider Jerry Eisert’s work for owner J. Frank Harrison, first in the 1966 Indy ‘500’ on May 30, 1966. Eisert was thinking hard about aerodynamic advantage when he created this huge ducktail on his No 96 Ford V8-engined car for Ronnie Duman:

Unhappily, Duman became involved in the startline multiple collision which shaped that race, and the Eisert-Ford was out of it before being able to demonstrate any form at all. But what’s this got to do with strutted wing development? Keep with me. Trawl again amongst the Library’s images, and here you’ll find more treasure: